It’s no secret: I’ve openly regarded therapy with skepticism at best and disdain at worst for a very long time. Justified or not, there are probably a few reasons for this:

I had a pretty lousy experience with therapy in college. The few sessions I attended made me feel pitied at one extreme and silly for complaining at the other extreme. At the same time, I wasn’t told anything I didn’t already know or hadn’t already practiced on my own, so the sessions felt useless. I also couldn’t shake the highly transactional nature of the relationship.

I’ll start with the positive here. The push to destigmatize mental illness, therapy, and psychiatric medications over a decade ago was very much needed, and I sometimes don’t appreciate it enough. Growing up, my community dismissed depression and anxiety as signs that one was not close enough to God, and that was usually the end of the conversation. The destigmatization movement was well-intentioned, and I’m thankful for it. In fact, some of the negative outcomes from this movement are still better than the previous status quo: the trend of over-seeking and -identifying with trauma is still better than the alternative, which is when people refuse to acknowledge and work through their traumas, terrorizing everyone with their unresolved issues as a result. (Think of the parents who claim it’s OK to hit children because they were hit and “turned out fine.”)

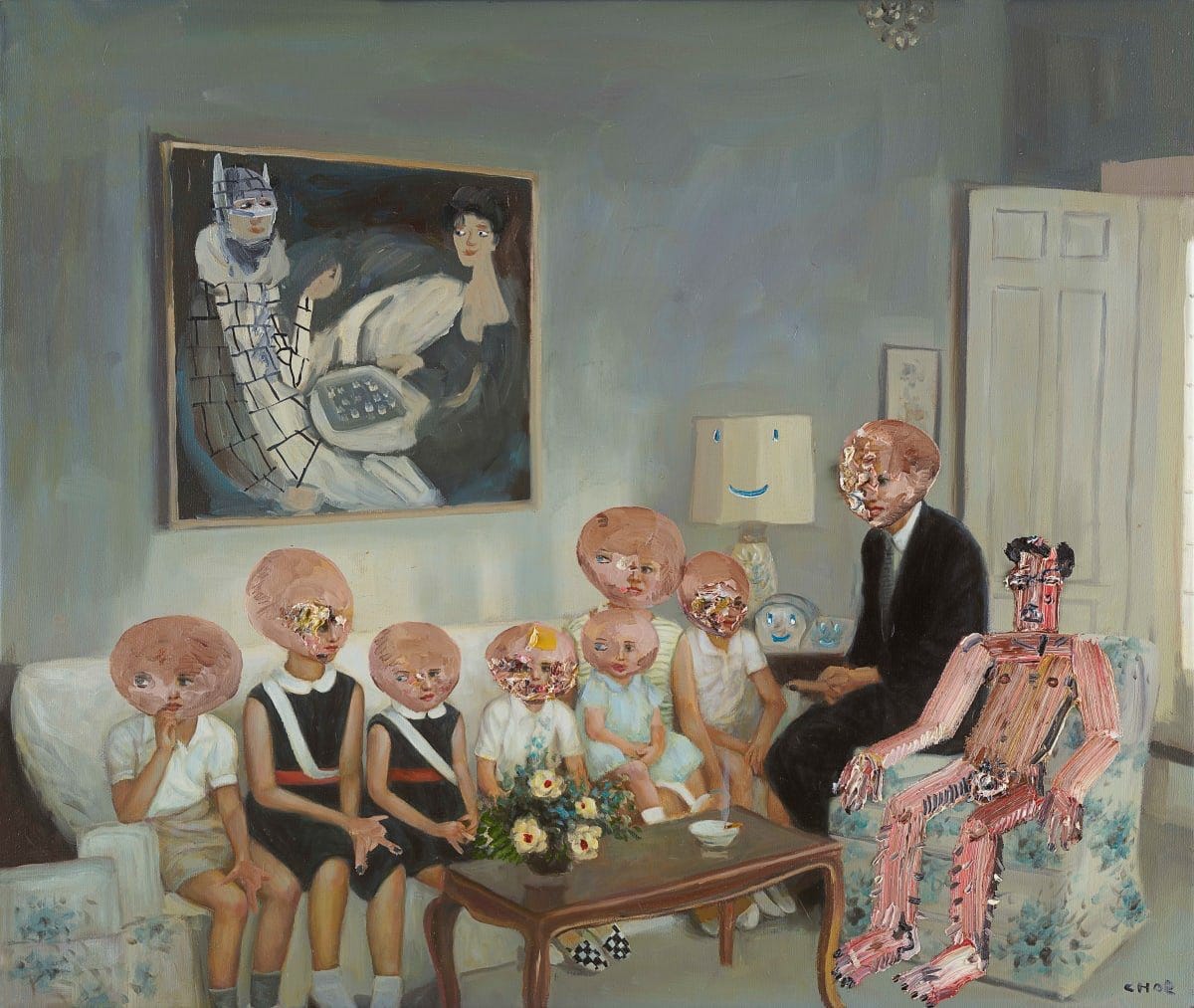

meticulously documents in her Substack GIRLS, psychiatric-related industries have pathologized every aspect of human life, preying on adolescents and young adults in particular. (Who else remembers the Betterhelp ad that shows a bunch of girlfriends saying it’s a red flag when a man doesn’t go to therapy?) We didn’t stop at destigmatization—we quickly moved to normalization and even glamorization, as I wrote in my previous post i’m broken, but at least i’m interesting. There’s a pervasive narrative that everyone could benefit from therapy. It’s also becoming increasingly taboo to question the efficacy and safety of psychiatric medications.

But things have gone too far, and it has given me pause. AsFor every good therapist, there is more than one bad therapist. I don’t know the ratio of good to bad therapists, but my guess is pretty cynical. (I’ll keep it to myself.)

points this out on his Twitter by highlighting the results of a study about so-called super-shrinks: “The therapists whose clients showed the fastest rate of improvement had an average rate of change 10 times greater than the mean for the sample. The therapists whose clients showed the slowest rate of improvement actually showed an average increase in symptoms among their clients.” The study found no significant differences in patient outcomes based on therapists’ gender, level or type of training, or theoretical orientation—suggesting that the differences in outcomes likely came down to the individual characteristics of the therapists themselves.

The study has significant limitations, but it invites us to ask critical questions: what makes a therapist bad, and just how harmful is it to be treated by one? Do super-shrinks exist, and if so, how can we develop more of them? We’ve all heard horror stories, like therapists who are unprofessional during Zoom calls, blur boundaries with their patients, refuse to push back on unhealthy behaviors, or encourage patients to think everyone else is the enemy. It might behoove us to consider that no therapist at all is better than a bad therapist.

All that being said, I am here to acknowledge my newfound appreciation for therapy. Specifically, for good therapists. No! For exceptional therapists.

It might seem obvious that exceptional therapists are impressive and should be appreciated; I knew that even at the height of my resentment toward the industry. But my understanding of exceptional therapists was limited by the fact that I had never seen or experienced, and therefore could not imagine, what this might look like—until I watched an interview with psychotherapist Nancy McWilliams.

Her ability to identify patients' specific personalities and health statuses, and respond accordingly, is phenomenal, and I have to share the insights from her interview with as many people as possible.

The interview is split into two sessions and is more than an hour and a half long (though not long enough). In this post, I’ll summarize the main takeaways from the first part of her interview, which defines 10 qualities of mental health.

This should provide a foundation for my next post, where I’ll share my notes from the second part of her interview—which was significantly more impactful for me. It explains the psychodynamic diagnostic process (a more nuanced approach to therapy and mental health than the system laid out by the DSM), including common personality types seen in therapy, how they manifest on a spectrum from high- to low-functioning, how each level on the spectrum should be treated according to research, and specific examples of therapist-patient interactions at each level.

I’m so excited to share these notes in my next post, but for now, let’s start with the fundamentals: what is mental health?

defining mental health qualities

Pop psychology might lead us to believe that the hallmark of mental health is happiness, but of course, it’s a little more complex than that.

According to Nancy McWilliams, there are 10 qualities of mental health. I want to summarize her account of these qualities to establish a foundation for my upcoming post, which will cover the different personalities prevalent in therapy and how a skilled therapist might approach each one in treatment.

Safety and attachment security

This is the ability to develop epistemic trust, or a “willingness to consider new knowledge from another person as trustworthy, generalizable, and relevant to the self.” This allows individuals to feel safer in relationships and experience joy and comfort around others, rather than solely torment. McWilliams highlights that one of the conditions for moving from insecure to secure attachment styles is having a devoted relationship of some kind that lasts at least five years.Self-continuation

An individual with self-continuation or self-constancy has a sense of being the same person across time, space, and within the body. Someone who struggles with this might react with bewilderment over questions like, what kind of person were you as a child? how do you see yourself in five years?—as if they were asked to describe a total stranger. They might not have the capacity to see both good and bad within themselves; they tend to define themselves entirely as one or the other.

Regarding the body, McWilliams says: “More and more patients I see seem to regard their body as a foreign object. You can cut it, burn it, starve it—as if it’s an it. They don’t feel fully embodied. They don’t feel like their body is ‘me,’ like it deserves for them to eat well or exercise well.” Someone who does not have a constant way of being recurringly experiences dissociation from the self.

I love this passage from Alan Watts’ essay Spirituality and Sensuality about the importance of integrating both the good and bad in oneself:It has often been said that the human being is a combination of angel and animal, a spirit imprisoned in flesh, a descent of divinity into materiality, charged with the duty of transforming the gross elements of the lower world into the image of God. Ordinarily this has been taken to mean that the animal and fleshly aspect of man is to be changed out of all recognition . . .

Not to cherish both the angel and the animal, both the spirit and the flesh, is to renounce the whole interest and greatness of being human, and it is really tragic that those in whom the two natures are equally strong should be made to feel in conflict with themselves. For the saint-sinner . . . is always the most interesting type of human being because he is the most complete.

Self-efficacy

This is also referred to as agency or autonomy. It’s the sense that one can make choices that influence his or her life. (I wrote about this in my post agency: it’s only human.) McWilliams points out that therapists typically notice self-efficacy when it’s lacking. A therapist might ask a patient why he married his wife, and he might respond, “I don’t know. It seemed like the thing to do at the time.” Similarly, one might ask a teenage girl if she felt desired when giving oral sex to a guy or if this act was something she wanted, only to realize that it never occurred to the teenage girl that sexual acts should be a result of her own desires.

Patients with low efficacy might shudder at a therapist’s suggestion to make their wants or needs explicit; their default tends to be an expectation that others should just know what they want or need and simply offer it—an unrealistic expectation that often breeds resentment.

They also tend to talk as though the world just happens to them. There is some truth to this—we cannot control everything. But McWilliams reminds us that even in extreme situations like the Holocaust, some people found small ways to reassert their freedoms. (Psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl’s book Man’s Search for Meaning is a fantastic example of this.)Self-esteem

The key here is self-esteem which is both realistic and reliable. Realistic self-esteem is exactly what it sounds like: having reasonably high and meetable standards to evaluate oneself. Someone with unrealistic self-esteem might feel bad if he or she falls short of perfectionism—or believe that everything he or she says is the ultimate truth that must be worshipped.

Self-esteem is reliable when it remains realistic and intact even in the face of criticism or high praise. Criticism of your work shouldn’t send you into a depressive spiral, and praise of your ideas shouldn’t inflate your sense of importance to an unrealistic degree.Resilience

This is also known as flexibility or affect modulation (i.e., the capacity to keep oneself within tolerable ranges, for instance between over-stimulation and under-stimulation). This typically requires an ability to rely on high-functioning defenses like humor and sublimation. McWilliams sums it up as “going through difficult stuff and still maintaining a sense that you’re going on being.”

We have a much better understanding of trauma than we do resilience. Why do some kids become stronger after difficult situations, while others break down in the same situation? I’ve been fascinated by this exact question for as long as I can remember. Resilience can be developed, but I often wonder how much of it can be tied back to upbringing or innate characteristics like personality.Self-reflection and mentalization

If you’re familiar with psychoanalysis, you might know this as insight into illness or the capacity to look at one’s own mind. Someone lacking this ability might struggle with questions like, why do you think you got triggered there? what’s the pattern for when you find yourself feeling paranoid? McWilliams recalls that in the past, it was believed that insight caused therapeutic change, whereas today, the belief is that insight tends to be the result of therapeutic change.

Another important aspect of mentalization involves the ability to imagine the subjective experiences of other people; this is known as the I-Thou relationship, in which one sees others as subjects with minds, not merely objects. Patients lacking this ability might struggle to imagine that their therapists do not intend to hurt them when questioning certain beliefs.Self vs. community advocacy

The spectrum between self-advocacy and adaption to the community is a recurring theme in clinical writing. People have needs for both, but each culture tends to emphasize one more than the other. Counter to what one might expect, psychologically healthy people don’t necessarily exist in the middle or lean toward the pole most adaptive to their culture. Rather, psychologically healthy people are strong on both ends of the spectrum: they can advocate for themselves when appropriate and subordinate their own needs to the needs of others or the community when required. This finding eliminates the temptation to pathologize cultures that emphasize one end of the spectrum over the other.Vitality

This one is my personal favorite, mainly because I’ve seen how devastating it can be when someone loses vitality. Recalling her clinical experiences, McWilliams says patients who lack this are the hardest to help—even harder than those who are furious at her. They tend to approach therapy with a defeatist mentality: let’s see if you can bring me to life; no one else can. Prove to me there’s any point in living life.

It’s not exactly depression, she says. It’s more like anhedonia. You might describe someone with an absence of vitality as being dead inside. It’s hard to find something that enlivens them. It’s hard to build a relationship with them that they consider meaningful because they’re in defense mode and nothing matters to them. Their natural enthusiasm, energy, and curiosity might have been discouraged or forbidden early on in their life, and they have yet to recover.Acceptance

This is the ability to accept what cannot be changed, like trauma endured at a young age. One goal of psychotherapy is to help people accept, rather than change, who they are. McWilliams stresses that this is not like positive psychology, which emphasizes happiness instead of the importance of tolerating grief and other inevitable negative emotions. “If you accept the stuff you can’t change and grieve it, you can move on to forgiveness and gratitude,” she says.Love, work, play

Love: can you love people as they are rather than idealizing them? Can you be devoted to their welfare? Can you make sacrifices for them? Do they exist as a subject to you, instead of an object?

Work: do you do something that has meaning to you, even if it’s difficult or not something inherently satisfying? Does your work make you feel like a contributor to your community? Does it make you feel like you matter?

Play: do you participate with others in sports, dancing, singing, and other activities? Are you making room for unscripted social engagements?

Many of these qualities might seem intuitive, but the language used in mental health discourse has gotten so convoluted that I think it’s important to establish clear definitions and goals for what constitutes mental health in the first place. The examples provided here really helped me understand these qualities and their significance at a deeper level.

I hope you enjoyed this post and come back for the next one, which I genuinely believe can be helpful to all who read it—whether or not they or their loved ones experience mental illnesses.

Very cool, excited for part 2!