i'm broken, but at least i'm interesting

on romanticizing mental illness and the stories we tell ourselves

The divide between the psychic hinterlands and a setting we might call normal is permeable, a fact that I find both haunting and promising. It’s startling to realize how narrowly we avoid, or miss, living radically different lives.

— Rachel Aviv, Strangers to Ourselves: Unsettled Minds and the Stories That Make Us

I love reading personal blogs and Substacks because I frequently come across a post so good that I think about it for weeks, months, and sometimes even years after reading it. I don’t know what it is about the personal blog format that does this for me; I rarely get the same satisfaction when reading pieces from seasoned journalists writing for traditional outlets such as the New York Times. Perhaps ideas click better when reading someone’s minimally edited thoughts and streams of consciousness.

Sometimes these blog posts disrupt my worldview and force me to scrutinize some of my long-standing beliefs. Other times, they put into words things I’ve always felt intuitively but never known how to verbalize; this allows me to connect and give purpose to the ideas floating around in my head.

Two years ago, I came across a post on Substack that had the latter effect on me. I’m still thinking about it, and now, here I am writing about it.

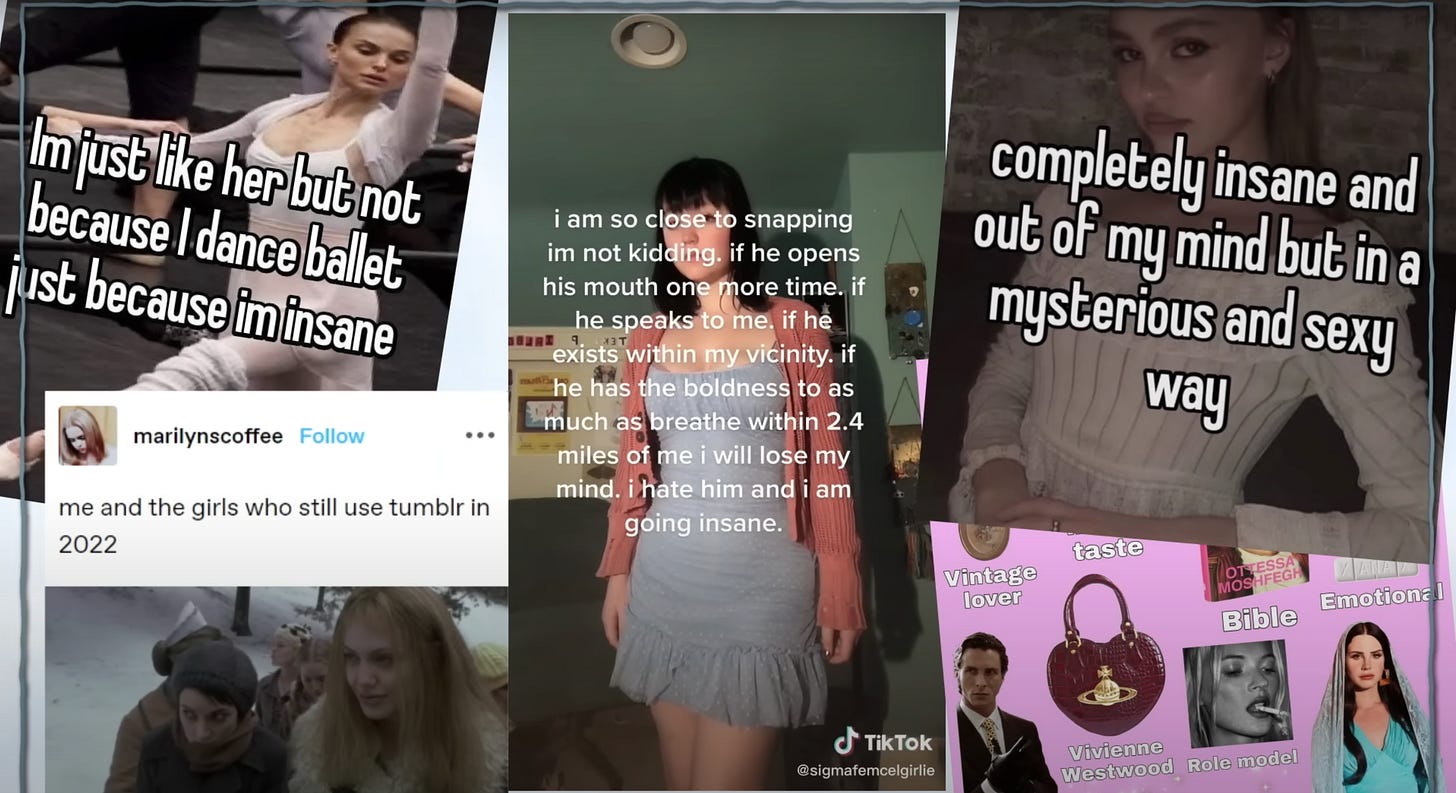

In her post Standing on the Shoulders of Complex Female Characters, Rayne Fisher-Quann talks about how easy it is for women to turn their neuroses, mental illnesses, and traumas into romanticized personas for online consumption.1 In just a few paragraphs, she perfectly articulates this trap into which so many women and girls fall. It’s a mindset that has been around long before my time, but one that I’m sure has been exacerbated by the continued proliferation of social media:

it’s easy, as a woman, to compactify illness into a consumable package — to whittle at the edges of pathology until it becomes little more than smudged eyeliner and wild sex. childhood trauma becomes daddy issues, suicidal depression becomes mystique. selling your pain is easier than living with it.

i am in my hysterical 20th-century woman era, i would think, unlikeably. i am sleeping at erratic hours, i am sobbing, i am writing and never publishing, i am seeing shapes in my wallpaper. i am never washing my face, i am eating lavishly, i am ruining my reputation. i am making sure to eat a square of dark chocolate during my depressive episodes so they’ll sound sexy in my memoirs. even when i am ostensibly at my lowest, i am still filtering my experiences through the eyes of a consumer; the desire to editorialize our own experiences (to romanticize the unseen, to live for our biographies) has become an autonomic facet of womanhood as unavoidable as breathing.

like the great mad women before me, i am spiralling into manic-depressive chaos in a way that i will inevitably romanticize regardless of its material consequences, and self-mythologizing until i can make that feel like a good thing. i’m not unwell or self-destructive or entirely unbearable — i’m in my fleabag era! we rationalize our own suffering through the romanticization of those who have suffered before us and, in turn, we provide a blueprint for the hot-girl suffering of those after. we commodify that rationalization through the era-appropriate medium. this is a cycle, apparently, that never ends.

To sum up my reaction in just one word: wow. The part about living for our biographies really stood out to me. Is viewing oneself through the lens of an audience (other women, men, future self, younger self, God, parents, whoever) largely a female trait? If so, is it predominantly due to socialization? Does this kind of external self-perception contribute to mental illness, and the romanticization of it? I showed my friend the passage from Rayne Fisher-Quann quoted above, and she said something I can’t stop thinking about: every time she writes in her journal, she writes as though an audience will later consume her entries. She doesn’t know why she does this, and she doesn’t know how to stop doing this. (And no, she’s not active online.)

YouTuber oliSUNvia shared a similar experience. Her pre-teen diary entries were extremely dark, but she admits:

I was a fraud. Yes, I was sad a lot. Yes, I had low self-esteem. But I wasn’t suicidal. I never had a real panic attack. It’s so embarrassing and disappointing to acknowledge that that’s how I once acted.

I thought that in order to give my sad emotions meaning, I had to make my sadness sound right. I couldn’t just scribble down diary entries however I wanted, with simple language and basic sentence structure. Who am I, Rupi Kaur? God, no. I had to write beautifully. Pre-teen Olivia made sure that her sadness was translated into words that sounded straight out of black-and-white, deep Tumblr GIFs. I needed my thoughts and feelings to be beautiful, because that’s the only time I saw society value mental illness: when it was delivered to us in the form of aesthetic art. In fact, I felt that to be deep and introspective, I needed to be sad. I had to be lonely and pessimistic in order to be truly enlightened about real life.

storytelling

This got me thinking about how so much of our understanding of ourselves is shaped by storytelling—even when that means pretending that the story we’re telling ourselves will one day be consumed by others (e.g., writing in a private journal that we, apparently, secretly hope isn’t so private). With that in mind, perhaps external self-perception is fundamentally human, and what makes way for mental illness is how much we externalize our self-perception, and how much of an identity we produce as a result.

In the book Strangers to Ourselves, Rachel Aviv explores the following questions: How do we understand ourselves in periods of crisis, especially when psychiatric explanations do not suffice? How do the stories we tell about mental illness shape their role in our lives and, consequently, our identity? She presents five case studies of patients who pushed past the limits of the psychiatric explanations of their times, and she includes interviews with the patients and their loved ones, published and unpublished passages from their journals and memoirs, and fascinating historical context about the development of psychiatry.

After reading Strangers to Ourselves, I realized that the romanticization of mental illness that Rayne Fisher-Qaunn illustrates is just a type of story we tell ourselves about who we are. It occurs to me that romanticization serves a few purposes, primarily by giving meaning to our suffering. It can help us:

cope with distress and instability, making our struggles more palatable to ourselves and others;

feel included in a community, since being “someone with [insert mental illness here]” can give one an identity and group of people with whom to relate, which might be easier than feeling alone and misunderstood;

attain status in certain circles where marginalization is seen as a social currency;

feel stronger, more interesting, or more complex than those who are not struggling;

succeed in intrasexual competition, which I’ll discuss more later.

But while romanticization might be a saving grace to some, especially in its earliest stages, it can also quickly contribute to one’s downfall. On her recovery from anorexia at the age of six, the youngest diagnosed patient at the time, Rachel Aviv says: “This sense of narrow escape has made me attentive to the windows in the early phases of an illness, when a condition is consuming and disabling but has not yet remade a person's identity and social world. Mental illnesses are often seen as chronic and intractable forces that take over our lives, but I wonder how much the stories we tell about them, especially in the beginning, can shape their course. People can get freed by these stories, but they can also get stuck in them.”

Reading Strangers to Ourselves made me realize that too much personal identity can be just as harmful as too little personal identity—and I think external self-perception and romanticization play some role in both.

Someone romanticizing her mental illness might identify too much with it, which can lead to a vicious cycle where her mental illness worsens, and resolving it could mean losing her identity, so the least disruptive option (in the short-term) is to continue identifying with her mental illness and building it out.

Someone externalizing her self-perception too much (e.g., extreme sensitivity about what others think, only viewing self through others’ perspectives, changing self for approval and to fit in) might have too little personal identity, leading her to rely on self-destructive behaviors and thought-patters to try to construct any identity. Here are some examples from Strangers to Ourselves of too little personal identity, and how this contributed to the rapid decline of mental health:

Hava, who struggled with severe anorexia her entire life, once wrote in her journal, "Labels aren't so bad. They at least give you a title to live up to... and an identity!!!" Many years later, she wrote: "I suppose I am one of those people that thoroughly understands myself yet am a stranger to myself. I'm not completely convinced I want to be rescued. Maybe it is just because I don't quite know who I am and what kind of person I am going to be."

Ray, who sued his psychoanalysts for failing to treat his depression and further driving him into illness, testified in court: "I'm not going to deny that I have had difficulties in living. I have looked at myself and examined myself from the viewpoint of a man who knows a lot about psychiatry now. Am I a narcissist? Am I really this? Am I not this? What am I?"

From poet Louise Gluck, on her struggle with anorexia: "The tragedy of anorexia seems to me that its intent is not self-destructive, though its outcome so often is. Its intent is to construct, in the only way possible when means are so limited, a plausible self."

Laura, who was given multiple diagnoses and cycled through 19 psychiatric medications (many of which she took simultaneously) over a decade, was relieved when she received a diagnosis: "It was like being told: It's not your fault. You are not lazy. You are not irresponsible. The psychiatrist told me who I was in a way that felt more concrete than I'd ever conceptualized before."

Whether the mental illnesses we identify with are genuine (e.g., the cases presented by Rachel Aviv) or performative (e.g., YouTuber Olivia’s pre-teen diary entries), so much of it has to do with storytelling. I want to talk about an interesting trend that has only been accelerating since I joined social media back in 2006: the mass storytelling occurring online that is romanticizing mental illness for young girls and women.

differentiating oneself

I first noticed this romanticization happening in middle school but didn’t put much thought into it until my late teens and early 20s, at which point I began to wonder why seemingly all the women in my life, online, and in media believed they were irreparably damaged. And their presentations of mental illness were rarely received negatively—they were often coveted. It’s as though we one day collectively decided to ignore the tragic consequences of mental illness, instead turning it into a social currency, different personas to be crafted for status, something cool.

There are a few different personalities that manifest from the romanticization of mental illness. I’ll lay out a few popular ones below. But first, some disclaimers:

The points made in this post are based on my personal experiences and observations. They do not apply to every woman and are not an indictment of womanhood.

Men romanticize mental illnesses as well, but I am not a man, so I will not focus on male experiences.

I am talking about trends that spread largely via social media platforms, so they will likely be more intelligible to those who are Online.

The purpose of this post is to talk about the different manifestations of the female romanticization of mental illness. It is not to debate the definition of mental illness. (See footnote 1.)

This post is not meant to imply that everyone who suffers from mental illness romanticizes it. In fact, those with debilitating illnesses that are less palatable to social media consumers (e.g., manic depression, psychosis, and schizophrenia) are considerably harmed by the trends that romanticize mental illness. Freddie deBoer does a fantastic job in his coverage of this (see The Gentrification of Disability or The Incoherence and Cruelty of Mental Illness as a Meme as a few examples).

I acknowledge that many people do not have mental illnesses. Still, it is interesting to consider that they are often derided as boring by those who romanticize mental illness: I came across a now-deleted TikTok that was on its way to becoming viral in which a girl questions why men frequently leave her—troubled yet interesting and complex—for simpler and uninteresting girls. She reveals a text from an ex-boyfriend who says he still loves her but that his new girlfriend is nicer, less complicated, and therefore better for him emotionally. Her confusion about his decision is revealing: it implies that being troubled should make you more interesting as a lover, and perhaps more worthy of desire.

Alright, back to business. Here are some common archetypes of the Mental Illness Romanticizers:

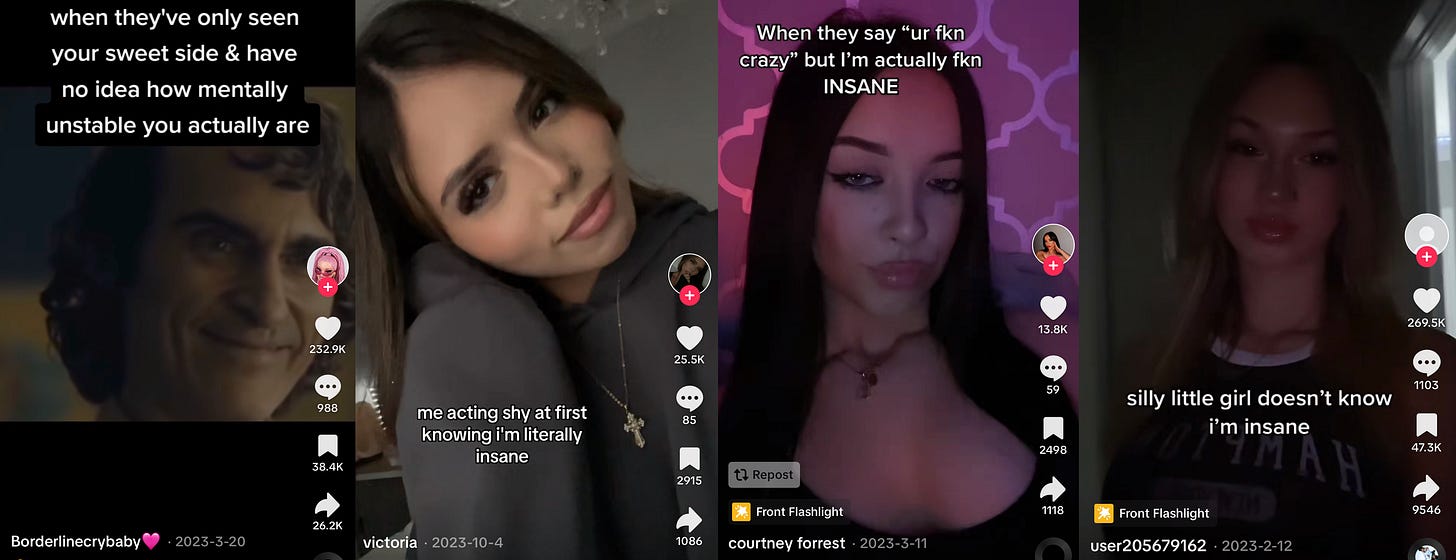

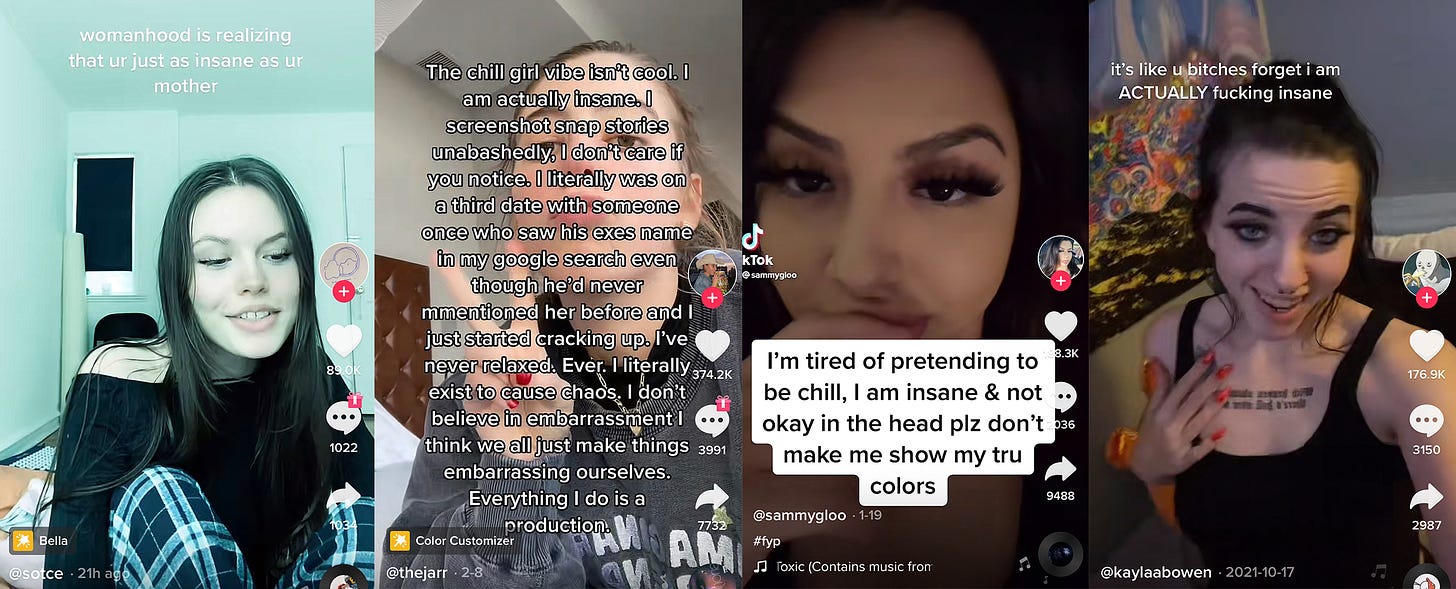

insane and proud

Lately, everywhere I turn, there is a woman smugly reminding the world that she is crazy. No, not just crazy, but insane. She’ll ruin your life if you get on her bad side. She’ll ruin the life of your next girlfriend, too, if you break up with her. She knows all the hottest tricks to permanently psychologically scar you. She’ll keep you on your toes; you’ll never know her next move. Being with her is a thrill, it’s dangerous, it’s not for the weak…

Okay, I don’t know how true all that is, but it’s exactly how the self-proclaimed insane women present themselves. Their declaration of insanity is seldom announced with shame, self-reflection, or hesitation. Rather, it’s a source of pride for them—and one can’t help but think they do this to appear more interesting and valuable to the men they are trying to attract. Incidentally, women often self-proclaim insanity in contexts related to men and female intrasexual competition.

You don’t have to dig deep to find thriving online communities that turn “insane” or contemptible women into highly sought-after aesthetics, relying on characters from books (e.g., literally any character from Ottessa Moshfegh’s novels), movies (e.g., Winona Ryder and Angelina Jolie from Girl, Interrupted or Rosamund Pike from Gone Girl), and TV shows (Alexa Demie or Sydney Sweeney from Euphoria, depending on the type of “crazy” that resonates with you most).

One popular term that describes this type of persona is femcel, which has been redefined from “female involuntary celibacy” to a celebration of toxicity and manipulation, but in a hyper-feminine way.

The clearest example is the clip below from HBO’s Euphoria. In it, Cassie, one of the show's main characters, brags about her insanity as a tactic to get what she wants from the man she’s seeing. She proudly screams that she’s crazier than her best friend Maddy—who is quite literally the blueprint for crazy. This is one of my favorite scenes from the second season of Euphoria, because in just 2 minutes and 58 seconds, we witness a perfect reenactment of the romanticization of being crazy and how it can be leveraged for intrasexual competition.

This is not limited to the theatrics of television dramas—the crazy girlfriend trope is regularly abused in real life by both men and women alike. Women might exploit the trope as a tactic to get and keep the men they desire; men might do so to absolve themselves of any responsibility for the failures of their relationships. There’s something else at play here too: a non-insignificant portion of men claim to prefer “crazy” women.

On X, I asked people to share their theories on why some men prefer to date unstable women. I was making an assumption here that there are men who prefer this—and I was right. So many men replied to my post or messaged me privately revealing their preference for unstable women. The reasons varied: for the emotional highs, for the wild sex, for the intellectual conversations, because of the hot-crazy matrix, because they’re more available, etc. These reasons, by the way, are widely communicated in TV shows, books, movies, and other media.

Why, then, should we be so surprised when girls and women take this to heart and develop personas around instability?

There’s no shortage of self-identified Insane Women And Girlfriends on social media platforms like TikTok. Many of these videos have millions of views, tens or hundreds of thousands of likes, and far too many comments from users claiming they can relate.

One TikTok claims that “womanhood is realizing that ur just as insane as ur mother.” Its most-liked comment finds a way to normalize this insanity, turning it into a virtue and welcoming its inevitably: “and perhaps that our mothers aren’t insane, just overworked, underappreciated, and can’t embody an impossible standard of femininity.” Sure, this is likely the case for some mothers who are labeled insane. But there are also a lot of mothers who are harming their loved ones and need help mentally. Where’s that conversation?

A lot of posts like these are (hopefully) exaggerated to achieve virality, but I have to wonder why so many young girls and women are positively engaging with them. If they are doing it because they can genuinely relate, then we should be very concerned about the current state of mental stability for girls and women. But I bet the vast majority of those making or agreeing with these posts are not insane.

So, is it just the aesthetic that’s appealing to them? Are they claiming insanity and then returning to their peaceful, non-insane, pretty normal lives? I think so. But if that’s the case, then there’s a more interesting question we need to contend with: At what point do exaggerations and false proclamations about oneself become… reality? When do the stories we tell ourselves become all-consuming and difficult to escape?

It’s not clear to me at what point the romanticization of insanity goes beyond just fun and games, and becomes a serious concern. But I think it’s time we turn the narrative around and clarify that Being Insane is not a good thing. That persona does not imply complexity or boost a woman’s self-worth and self-efficacy. Ultimately, it becomes a net negative for the woman herself and everyone else in her life.

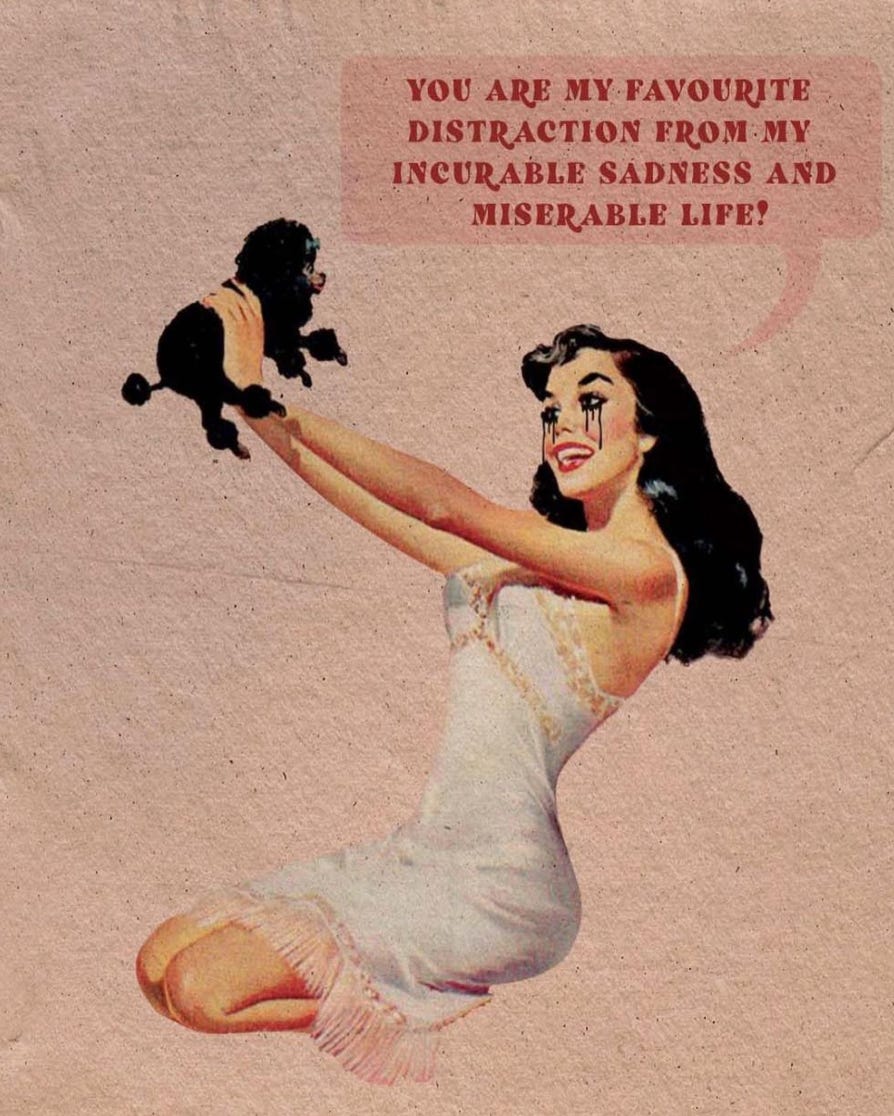

woe is me

Another ideal candidate for the romanticization of mental illness might be one with a victim mentality. I’ve written (and posted) about how victim complexes rob people of their agency, and why the immediate benefits of perpetual victimhood, like avoiding accountability, are ultimately never worth it:

A victim mentality is one of the biggest threats to cultivating a sense of agency. Perpetual victimhood cannot coexist with agency.

To be clear, I’m not talking about horrific events and circumstances that produce victims (or survivors, as some people prefer to say). Thinking of someone—or yourself—as a victim in certain cases can be a useful framework for finding solutions. I’m talking about people who unproductively cope with adverse life events by refusing to take accountability and instead blaming anyone and anything else for their woes; it’s a comfortable position to be in because someone with a victim complex can avoid responsibility, garner sympathy, and always find a way to justify their harmful behaviors. The crux of the mentality is the absence of agency.

Reminder that a sense of agency means feeling like you have control over your actions and their consequences. I think people tend to forget that second part; owning your mistakes and their consequences is extremely difficult, which might be a motivating factor for some people to adopt victim complexes. (A victim complex is learned!)

This is where the Sad Girl persona that YouTuber Olivia developed in her pre-teens comes in. As Rosemary Kirton defines it in i-D magazine, a Sad Girl “listens to better music than you and might spend her alone time watching French films from the ‘60s or angsty TV shows from the ‘90s.” She might obsess over the lives and works of Sylvia Plath and Virginia Woolf—ignoring the devastating and life-threatening nature of their Sadness, and instead inadvertently turning it into a conduit for creativity, intelligence, and societal reverence. Talk about romanticization!

With so many examples of female sadness, you begin to wonder if a woman is less of a woman—less interesting, complex, desirable—if she isn’t fighting any demons, or overcoming (or succumbing!) to her traumas. You also begin to wonder if suffering is uniquely female, rather than inherently human. By accepting and internalizing this idea, women rob themselves and men of their autonomy: women are no longer agents of their life, they are slaves to the things that happen to them; men are no longer complex human beings also capable of experiencing the full spectrum of emotions, they are merely two-dimensional characters struggling to understand their more complex female counterparts.

In another one of her posts, The Pain Gap, Rayne Fisher-Quann nails why this romanticization of trauma might be so ubiquitous for women:

there is a sickeningly pervasive idea in our culture, by the way, that a young woman can only become interesting and complex by experiencing untold quantities of pain — and so we seek this suffering in an attempt to become artistic, but only end up learning that we were operating from a flawed premise in the first place. pain is nothing but pain.

If this is true, and I suspect it is, then it’s no wonder why so many young girls and women find solace in this romanticization. Whether it’s to gain a (false) sense of control over their life or to appear as interesting and complex as the women they admire, the appeal has been manufactured for them, and it’s hard to resist.

daddy issues

This one is especially devastating, in my opinion. It’s also much harder to write about because there’s always the risk of unintentionally slut-shaming or talking about sexuality in a reductive way. But the romanticized persona is really hard to miss. It might include the aesthetics of Lana Del Rey and cigarettes, coquette, Lolita, hypersexualization, fetishes, being wild, sugar babying, infantilization, identification with borderline personality disorder, etc. I might have more to say about this another time, but I did want to include it here since it’s one of the more popular manifestations of romanticized mental illness online.

everyone is implicated in this…

And I’m worried this includes writers like me who are lamenting over the issue. Is it possible that writing about the romanticization of mental illness is making it more of an issue than it already (or really) is? Maybe. I wish I could track the popularity of this romanticization over time to see if it’s on the decline or not. But for now, all I know is that I’m still seeing it everywhere, from social media to traditional entertainment. And it’s constantly evolving, so new iterations might be harder to catch at first, but the outcome is ultimately the same: social media engagement and surface-level relatability at the expense of human flourishing.

If you’ve come this far, thank you. I’d love to hear your thoughts about this post—I’ve been thinking about it and writing and re-writing it for a very long time now, but decided that it’s time to publish and hear from others rather than spend more time trying to perfect it.

I’m going to be using the words “mental illness” a lot throughout this post. I understand that there is no one clear definition of mental illness, and our understanding of it is constantly evolving. I want to acknowledge this, but defining mental illness is beyond the scope of this post. It’s best to think of it in terms of how it’s widely used and accepted today.

A few random thoughts: it reminds me of the line from american beauty where mena suvari says "I don't think that there's anything worse than being ordinary." Women would rather be crazy which makes them interesting, than boring/ordinary.

There are less avenues for women to be interesting than men so maybe they over index on this avenue. For example more men play sports which even if you don't think is interesting, they think it makes them interesting.

Women seem to identify as "artists" more than men, and great art has a storied connection to pain/insanity.

Manic pixie dream girl also comes to mind.

Is it too cynical (or much too reductive) to reduce it to competitive performative attention seeking? Drawing a throughline via "femcel" is great inasmuch as this sort of romanticization of mental illness is a mirror to the nice guys of yesterdecades; when one can't compete in the "normal" arena the generically obvious next step is to try to stigmatize normal and distinguish oneself therefrom. I'm not like those dumb, brutish jocks, I'm nice and gentle. I'm not like those vapid, airheaded barbies, I'm edgy and crazy. Sides of the same coin, perhaps?