grieving someone who is still alive

what happens when the person we are mourning is still very much alive—perhaps even still in our lives?

Grief is a complex emotion to navigate, but there is some comfort in the fact that it is inevitable. We will all one day have to mourn the death of a loved one, and others will do the same for us. But what happens when the person we are mourning is still very much alive—perhaps even still in our lives?

I think about this type of grief a lot. This emotion is far from foreign to me, and as I grow older, I’m realizing that more and more people have experienced it or are currently going through it as well. (I am once again reminded here that we are not alone in these experiences, finding both sadness and comfort in this realization.)

On the lighter end, you could feel some amount of grief when you and a close friend drift apart over time, becoming strangers with a history. You might also experience this type of grief for your past or future self, but this topic requires an entirely separate post.

On the more extreme end—and this is the type of grief I want to talk about in this piece—it could happen when a loved one undergoes a significant negative change that transforms who they are as a person, or you find out something about them that entirely changes how you see them, leaving you completely at a loss for what to do.

This post is my attempt to understand why we experience grief when this happens, especially for such an extended period of time. My theory is that we experience this type of grief precisely at the moment when we start to realize this person has fundamentally changed, because our mind desperately wants to cling on to the person they used to be. At this moment, we find ourselves stuck trying to reconcile the past (who they used to be) with the present (who they are now). And sometimes, we’ll rationalize or dismiss their behavior for temporary comfort.

I think this mostly comes from a place of love and loyalty, but part of me also worries about the consequences of finding ourselves stuck here for too long. In the next section, I’ll try to explain my understanding of this emotion, but I recognize that I might be off—and I definitely have more questions than answers. If you have other theories, I would love to hear them!

When we meet someone for the first time, we construct an image of this person in our heads. And whether we realize it or not, this image is updated with each subsequent interaction we have with this person. (Of course, this is a bit more complicated for people who have always been around, like family members, given that we begin constructing this image from childhood—a time when we have little life experience to best inform the image we’re creating. Similarly, this image creation process applies to ourselves, which means we can also experience grief for our past selves when we go through a monumental change.)

Are they trustworthy? Do they like me? Are they fun, intimidating, confusing? How do I feel when I’m around them? Who do they remind me of, and what other similarities do they share with this person? Are they still trustworthy?

And on, and on, and on.

As our relationship with someone deepens and becomes more complex over time, so too does our image of them. Suddenly, this image includes thousands of little updates and revisions due to good and bad memories, solicited and unsolicited input from other people, projections of our desires and expectations and insecurities, plus a number of other factors—and with enough time, this image sticks.

It becomes increasingly difficult to make any updates that might strongly contradict our existing image of this person.

I believe this specific instance is when we experience this unique grief for the living—when the contradictions are too overwhelming for us to accept or peacefully incorporate into the image we’ve created of someone, making us feel like we’re stuck.

I’m not talking about the inconvenient but minor updates that we make all the time, such as realizing that someone is always late rather than punctual, or is messy rather than clean, or hates your favorite show or music genre, or is not always aligned with your political beliefs, or is naturally changing as they mature. These realizations simply help us see others as real people who exist outside of our projections of them. In a way, these updates are good, and in many cases harmless!

Instead, we experience this grief when something happens that requires a complete reassessment of the person in question; when the only way to understand and accept who they are now is to stop clinging on to our image of who they used to be.

Physically, the person is the same—psychologically, they might as well be a stranger.

Hopefully, an experience like this is rare. It might happen when someone you know struggles with addiction (the HBO show Euphoria depicts this transformation really well); changes due to severe mental illness; becomes abusive, cheats, or betrays you… you get the point. A change that is more shocking or distressing than the inevitable changes that people go through over time.

These changes, for lack of a better term, might happen suddenly or gradually. For example: finding out your partner cheated might be a sudden change that causes you to grieve the image you had of them, while watching someone you love fall into an addiction might be a gradual change that also causes grief and a reassessment of how your relationship should function from that point.

But it is then—once we are made aware of the change(s)—that our image shatters and we experience this unique type of grief, finding ourselves stuck trying to reconcile our “before” image of the person with the new information we’ve gathered.

What causes us to be stuck here? And why do some people stay in this stage for months, years, or even a lifetime? One obvious answer is shock, or denial. But to dig a little deeper: I think most of us are scared to let go of the “before” image, because doing so metaphorically kills off the person we used to know. And death in any form is an uncomfortable topic; one that we have not yet, and perhaps will never, come to understand or make peace with. There’s also the fear that we’re giving up on someone we love, so we find (sometimes unhealthy) ways to revive our hope in this person.

This happens in the stuck phase, when we’re still trying to grapple with the change(s).

It might especially be difficult for us to move past the stuck phase if the person still exhibits characteristics from the “before” image we hold of them—and they most likely do. We might feel stuck because these characteristics elicit memories which give us hope that this person didn’t actually change.

I’m particularly interested in how we can come to terms with these changes and move past the stuck stage. Perhaps then, our assessment of the person can be more realistic, allowing us to approach our relationship with them in a healthier or more productive or less emotionally distressing way. Or to leave completely and find peace in our loss.

Obviously, a lot of context is required here; each solution will be as unique as the situation it is addressing. Maybe acceptance is the answer for this type of grief. Or maybe the right answer is to keep fighting and not lose hope. Maybe it’s something else entirely.

What’s interesting here, and perhaps a topic for another day, is the perspective from the person who is undergoing the change(s) we talked about. After all, there is some truth to the idea that people leave when you need them most, when you are going through a very difficult time, when you are at your most broken. In part, it could be because difficult times can bring out the worst in people; it also could be because difficult times really are a true test of loyalty. But this shift in perspective raises a lot of questions for how to best deal with this situation. Again: do you leave? Do you accept the situation? Do you try to solve it? Do you fight for change? How do you balance your needs with the needs of the person you’re grieving?

The point I’m trying to make: I have no idea what the best approach is for handling this type of grief, and I don’t know if there is one. In fact, at the moment, I’m okay accepting that this type of grief is just part of the human condition—an experience that we can’t hack or eliminate.

At the same time, I’m hopeful that these experiences, while difficult, don’t have to destroy us. To end this post on a more hopeful note, here is a lovely quote (of a quote) from one of my favorite books, The Telomere Effect:

As Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a Swiss psychiatrist who studied grief and mourning, once said: The most beautiful people we have known are those who have known defeat, known suffering, known struggle, known loss, and have found their way out of the depths.

These persons have an appreciation, a sensitivity, and an understanding of life that fills them with compassion, gentleness, and a deep loving concern.

Beautiful people do not just happen.

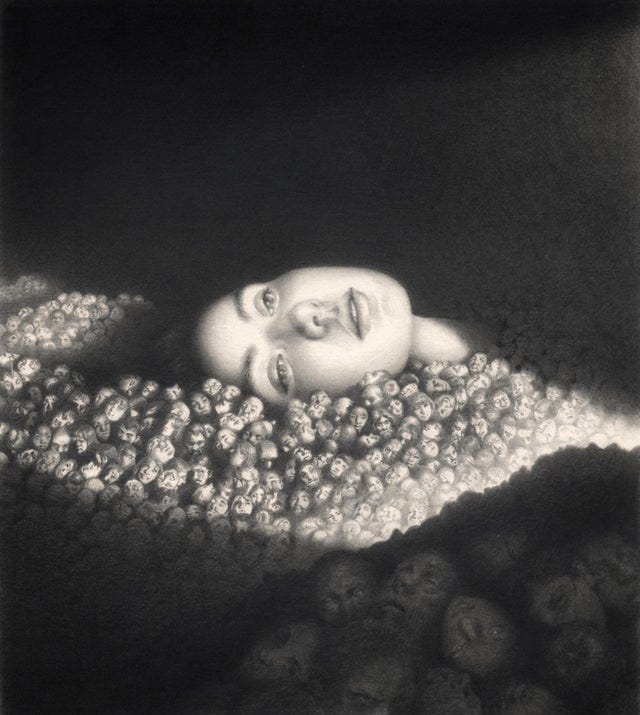

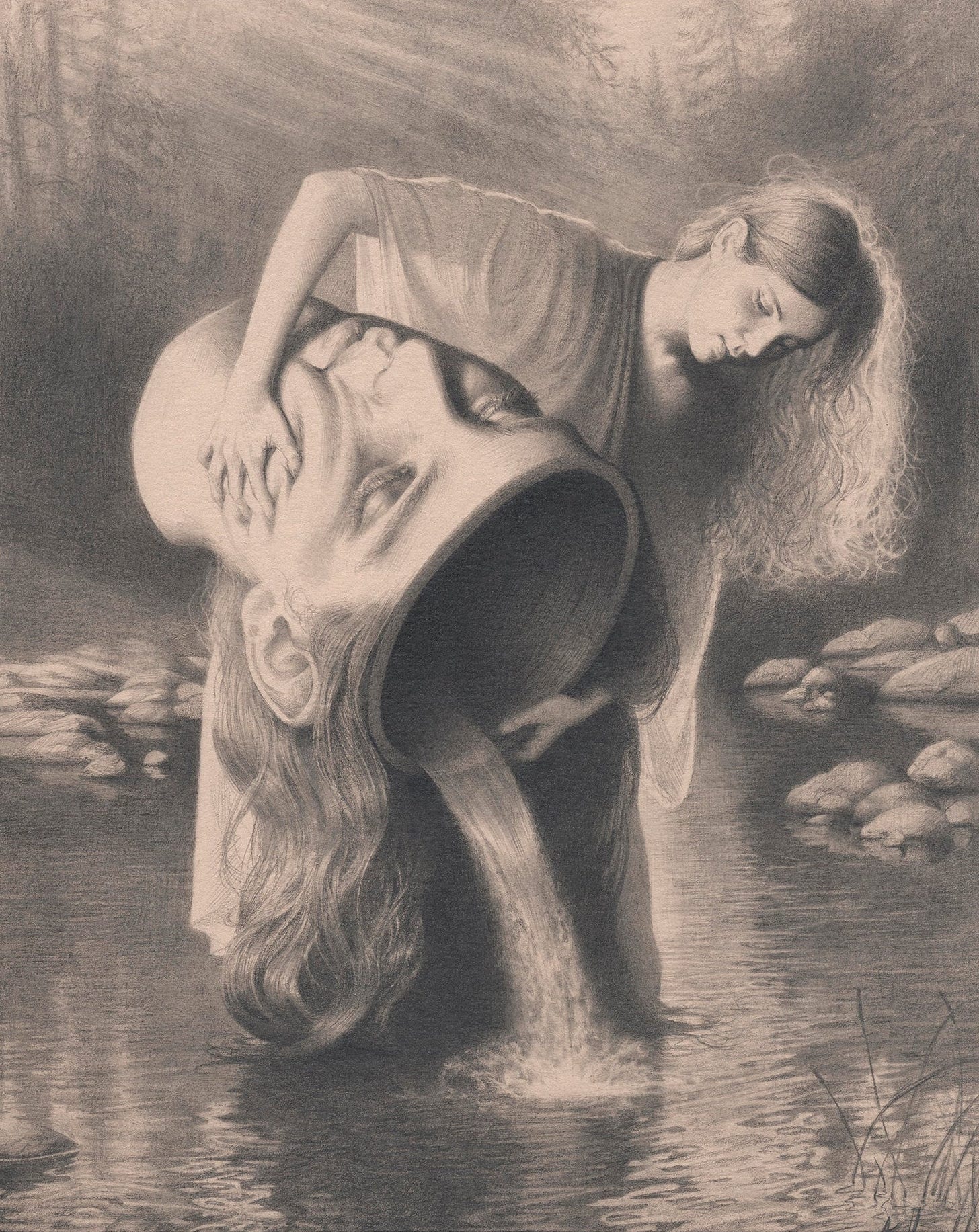

final thoughts, but in art form

There was a lot left unsaid in this piece (and definitely more questions raised than answered), largely because this is a complex topic with little written about it, and it’s rare to find someone who has successfully navigated this type of loss and found peace with it.

Art helps bridge the gap between the feelings we can articulate, and those we cannot. Here is my attempt to bridge that gap. I hope you enjoy some pieces that really resonated with me while writing this post:

Found this post through Twitter; really interesting topic.

I feel like you're trying to define what it means to lose someone. That loss can have many causes, but I think what all your examples have in common is that they all involve having a source of happiness that goes away.

Why particular people get stuck is mostly a psychological research question (do addictive personalities have a tendency to get stuck? does emotional regulation control the effect?), but I think a more interesting question is WHY does ANYONE feel loss? What exactly are we losing, and why does it hurt so?

I think it's probably tiny intimacies, little valuable personal secrets, that we really mourn. It hurts when we know there is no longer a person in the world who says "okay" in their strange, but uniquely charming, way or when we know that we will never again hear their awkward but comforting responses to our complaining. These things are equally destroyed by death, by radical change in someone, or by destruction of an intimate relationship.

Why do we mourn these things? To some extent the answer is just "evolution," but that is not particularly satisfying (and is more "how" than "why"). I wonder if we value these things, exactly as Kübler-Ross says, because coming to appreciate them is what makes us grow into complex, beautiful people.

Beautiful