Have you ever been confronted with an idea that challenged your worldview so strongly, that it was inconceivable for you to even consider adopting it—only for you to later, perhaps under different life circumstances, adopt that exact idea?

What exactly is going on here?

In his book Escape from Freedom, German psychoanalyst and philosopher Erich Fromm talks about the conditions needed for an idea to be adopted on a societal scale:

If we analyze religious or political doctrines with regard to their psychological significance we must differentiate between two problems. We can study the character structure of the individual who creates a new doctrine and try to understand which traits in his personality are responsible for the particular direction of his thinking. […]

The other problem is to study the psychological motives, not of the creator of a doctrine, but of the social group to which the doctrine appeals. The influence of any doctrine or idea depends on the extent to which it appeals to psychic needs in the character structure of those to whom it is addressed. Only if the idea answers powerful psychological needs of certain social groups will it become a potent force in history.

— Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom (pgs. 64 - 65; emphasis mine)

On the surface, this seems obvious; of course one is more likely to adopt a worldview that they are psychologically primed to believe. But the power of understanding if and why an idea will be adopted—on an personal, interpersonal, and societal level—is tremendous.

on a personal level

Without going into too much detail, I want to give a personal example of what this might look like on an individual level.

It’s no surprise that, after years of witnessing domestic violence, I found the viral #MenAreTrash and #YesAllMen movement so appealing. Nothing could convince me that there were, in fact, good men out there. I was not psychologically ready to hear anything other than a quick and cheap validation of my personal experiences.

Accepting the conflicting idea that #NotAllMen are bad would have meant one of two things for me:

(1) I accept this conflicting worldview and am motivated by it; I actively seek out examples of good men and bring them into my life

(2) I accept this conflicting worldview and grow resentment because of it, wondering why it couldn’t be the case for my life

The easiest approach, of course, is to completely reject this conflicting idea altogether and continue on believing that my worldview is correct, completely unchallenged. This is what I did for some time, and what I suspect many do when they are hurt or feel as though they lack agency.

Option (1) from above seems like a great choice, but I can think of a few explanations for why someone would not choose it:

it requires a lot of effort to reassess one’s worldview in a healthy way, and it can sometimes even be a painful experience

if you are completely preoccupied with survival, you simply don’t have the time or mental capacity for introspection

if you lack some level of agency (e.g., you’re a minor), motivation resulting from a change in perspective simply might not be enough to better your life

I abandoned this worldview many years ago. To borrow from Fromm’s idea, I was psychologically ready to give up this worldview when I did: I was several years removed from any direct threat, gained a significant amount of independence, was finally surrounded by great men, and could afford to let go of the bad ones. More importantly, I had agency.

So when I was confronted, once again, with this conflicting idea that not all men are bad, I was able to seriously consider if it was true or not—if it was a worldview I wanted to believe in. And I did. It took some work, but I could not have accepted this conflicting idea if, at some psychological level, I did not have a need for it.

This is a lesson for me: having some awareness of the reasons behind the worldviews you hold and have never questioned can be really helpful, especially if you’re trying to effectively navigate the world and improve your perception of it.

on an interpersonal level

Here’s an example that might resonate with many people: Have you ever tried to convince your friend that they should leave a horrible relationship, but felt like you might as well be speaking to a wall?

Your advice might be correct, but once again, adopting it would require your friend to essentially dismantle their worldview. Your friend would need to abandon their belief that their relationship is worth salvaging for whatever reason, for your belief that they are being mistreated and should find a better partner.

As mentioned, this requires a lot of effort and can be painful—rationalization might be uncomfortable, but it’s a far easier approach to take. (That is, until the cognitive dissonance becomes so overwhelming that one is forced to make a change.)

The lesson here? It’s all about timing. One day, your advice might just click for your friend, and they will begin to slowly improve their life. Understanding their needs and motivations for upholding certain beliefs can help you navigate tricky situations like this and better understand why people believe what they believe. (Note: patience and compassion required!)

on a societal level

This one is a bit trickier to discuss, but it’s important to consider why some ideas immediately spread like wildfire, why others take time to be adopted, and why some just never gain steam.

One of the most fascinating examples for me is the Me Too movement, especially because of its overlap with strong anti-men sentiments like Men Are Trash.

It goes without saying that the Me Too movement has its merits. It was perhaps the first time people saw just how widespread sexual harassment and assault is—that it could happen to anyone and isn’t as clear cut as being raped by a stranger in a dark alleyway. With the viral movement came a number of thoughtful discussions about consent, finding support after assault, and identifying truly predatory behaviors. There were even some tangible changes.

Why did the Me Too campaign—originally created by activist Tarana Burke back in 2006 to raise awareness around abuse and sexual assault—take 11 years to catch on? One simple explanation could be that social media was not around in the same way back in 2006, so it was harder for a movement to become so big. But that reason is not good enough for me.

Which of society’s psychological needs was Me Too tapping into when it went viral? It goes without saying that there were obviously frustrations around rape and sexual assault. But what else?

Here are some initial theories I have, which I recognize raise more questions than answers, but I am interested in exploring and (respectfully) discussing them further:

As we move more toward a more individualistic culture, movements increasingly need to have some element of relatability in order to be virally successful.

The goal of Me Too was always, first and foremost, to raise awareness around the magnitude of sexual assault. And while there are many examples of awareness movements that go viral with the help of people who can’t relate to the issue at hand, I imagine virality is much more attainable when a large segment of the population feels included and can share their personal stories of being affected.

And there’s the key word: feeling included. Perhaps at a time when more and more people are suffering from an erosion of community, there is a deep-rooted psychological need to be included somewhere—to be part of a community. And what feels more fulfilling than being part of global community, one that is also promising to make the world a better place? Whether you were catcalled, made uncomfortable during a date, sexually assaulted at work, or raped by someone you thought you could trust, there was a place for you to go and not feel so alone.

(Regarding the distress of not being part of a community: there is a great TikTok about this—part one here and a more relevant part two here. I highly recommend you watch them and read the comments.)

For better or worse, traditional relations between men and women have been breaking down for a while, creating a vacuum in which tension and confusion between the two flourish.

There’s good that comes out of letting go of outdated gender roles. But all transitions come with a period of turmoil. The movement overlapped with (and fueled) a widespread, negative sentiment against men. Men weren’t just trash, they were also knowingly or unknowingly perpetrators and upholders of The Patriarchy. It’s not surprising, then, that a movement like this could resonate so strongly with someone holding a grievance against one or two or all men.

For clarity, this is not a commentary on the original purpose of the movement (to raise awareness around a legitimate issue) or whether or not those with grievances were justified. I’m more interested in why the movement succeeded when it did. What psychological needs was it fulfilling? What void was it tapping into? Could it have succeeded under slightly different circumstances? Changing gender norms and long-time “discontent with men” finally erupting into a global movement is one possible theory.

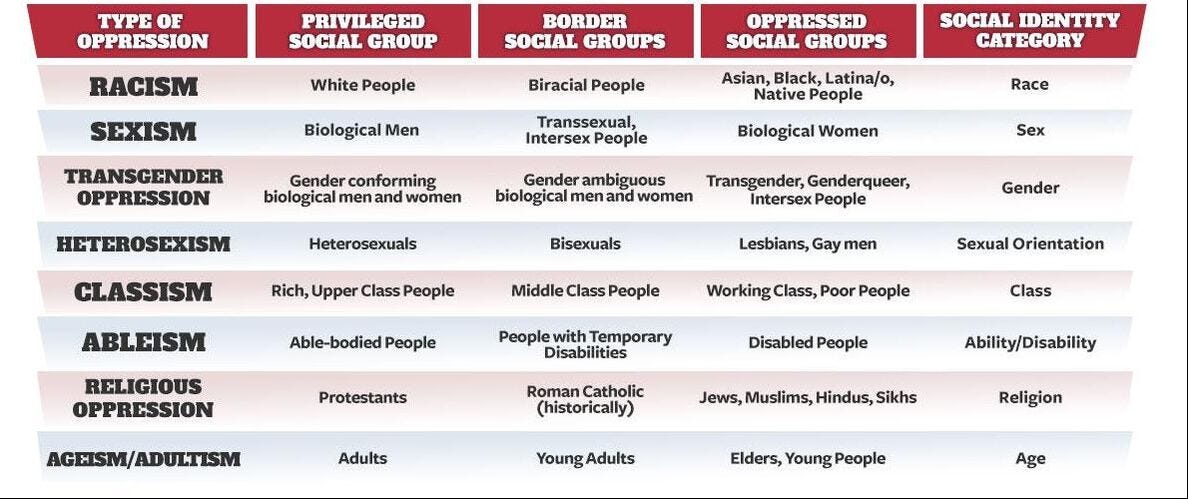

When people are defined by how privileged they are—and (de)valued accordingly—being able to claim some level of oppression is an incredibly valuable social currency.

Everyone I know, whether they lean left or right, acknowledges something called The Oppression Olympics—an interesting phenomenon in which people compete to be the most marginalized person, a position that can offer both personal validation and a platform for social commentary.

Simply posting the #MeToo hashtag signalled to the world that this person experienced sexual harassment or assault and is, to some degree, marginalized. It’s not clear to me yet how empowering—in the true sense of the word—this is, and I don’t know if we’ll ever truly know, but I’m more interested in the extent to which this signalling contributed to the virality of the movement.

Could Me Too have succeeded in the same way if, psychologically, people did not want to identify with their oppressions or traumas? Or if there was no motivation or incentive for this type of signalling? What need was being fulfilled via this signalling?

final thoughts

Fromm’s quote was incredibly influential for me. It made explicit a thought that I always had but was not consciously aware of: that we are capable of changing our worldviews, but the timing and psychological circumstances matter.

I’ve seen it happen to me, my loved ones, and while observing people and social groups from afar—but making use of this new theoretical framework can help me (and maybe you!) navigate the world a bit better.

Hopefully the pandemic creates psychological needs to be connected and have community amirite???

Great writing, thought provoking. Thank you.