what does anything mean anymore?

a complete overhaul of our moral frameworks, and thoughts on dignity

I often find myself listening to an argument or reading a heated back-and-forth between two people and realizing that they are entirely talking past each other, which renders their debate interminable. Few, whether active participants or quiet observers, will leave such arguments feeling accomplished, fulfilled, or like they have learned anything new. More often than not, they will leave more intensely attached to their position and dismiss the opposing side as unethical, ignorant, or [insert trending character attack here].

Unbeknownst to them, they will repeat this exact charade of a debate countless times, each time less productive than the last.

Sometimes, it might appear as though the debaters are on the same page about what they are debating: they use the same words and phrases, and they might even anticipate each other’s arguments. But if you dig a little deeper, you will quickly find that there is no consensus on the very words their arguments rely upon! If you asked the debaters to clearly and accurately define certain words in their arguments, they might realize they do not have a complete grasp of the concepts they are debating.

This is especially the case for arguments involving complex and abstract ideas like justice, human rights, dignity, harm, eugenicism, or misogyny—words used in nearly every debate that seems to have no end or resolution in sight. Whether the debate is about abortion, gun rights, interventionism, gender theory, or healthcare, the opposing sides never seem to reach a satisfactory or productive conclusion—regardless of how knowledgeable, kind, open-minded, or reasonable the debaters are. At some point in the debate, tensions will rise, people will begin to feel threatened, and the debate will cease to progress.

This has become such the norm that many might believe these debates inherently cannot be solvable; that they are interminable by nature. But how true is that?

Was it always like this? And if not, how did we get here? And at what point should we consider this state of affairs a serious crisis that needs to be addressed?

a catastrophe

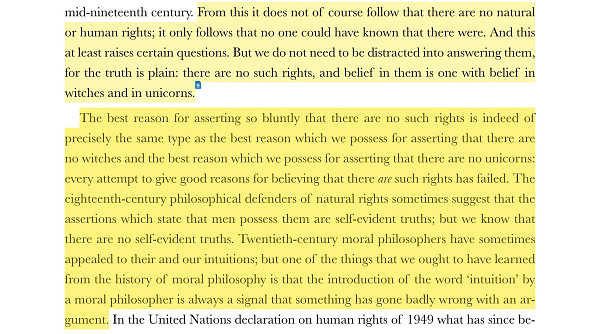

In his book After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, Alasdair MacIntyre attempts to answer all of these questions. He hypothesizes that our moral debates do not and, in fact, cannot find a resolution today because we have unknowingly lost our comprehension of morality but nonetheless continue to use its concepts and vocabulary.

To illustrate how this could have happened, MacIntyre asks us to imagine a society in which a popular political movement takes hold and successfully abolishes the natural sciences: labs are burnt down, scientists are imprisoned or executed, science classes are banned in schools, and science books and instruments are destroyed.

Eventually, a group of enlightened people mobilize to revive science, but their knowledge of the sciences is largely incomplete. They might know a few important scientific experiments, but they cannot connect this knowledge to the context that originally gave those experiments significance. They might know some key scientific theories, but their knowledge is incomplete and they only have half-chapters from science books and single pages from science articles. Still, their fragmented knowledge became the basis of science in their society; in their view, the natural sciences have been fully restored. Individuals in this society go on to study and debate scientific theories and systematically use the scientific words and expressions of the past, while children are taught and tested on science lessons in school.

While it might appear as though the sciences in this society are thriving, things are, in fact, quite dire: “Nobody, or almost nobody, realizes that what they are doing is not natural science in any proper sense at all. For everything they do and say conforms to certain canons of consistency and coherence and those contexts which would be needed to make sense of what they are doing have been lost, perhaps irretrievably.”

As a result, something interesting begins to happen in this hypothetical society. Because scientific knowledge is unknowingly incomplete, people start arbitrarily using scientific words and expressions, and irresolvable arguments become commonplace. (Let’s jump back to reality real quick—does this sound at all familiar? It should, assuming you have been paying a little attention to any moral debate. Alright, back to the imaginary society.) Suddenly, subjectivist theories of science begin to appear, and society becomes divided between those who believe their science is objective and those who espouse the subjectivist theories of science.

MacIntyre concludes this imagined scenario by comparing it to the current state of moral language and philosophy in the real world:

What is the point of constructing this imaginary world inhabited by fictitious pseudoscientists and real, genuine philosophy? The hypothesis which I wish to advance is that in the actual world which we inhabit the language of morality is in the same state of grave disorder as the language of the natural science in the imaginary world which I described. What we possess, if this view is true, are the fragments of a conceptual scheme, parts which now lack those contexts from which their significance derived. We possess indeed simulacra of morality, we continue to use many of the key expressions.

But we have—very largely, if not entirely—lost our comprehension, both theoretical and practical, of morality.

— Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue (pg. 1)

Part of the problem, MacIntyre hypothesizes, is the widespread belief in something called emotivism, which is the idea that all claims of moral truth are in reality expressions of personal preference and feelings. According to this theory, when someone says something is bad or wrong, they actually mean they personally condemn it. Similarly, when they say something is good or right, they actually mean they personally like or prefer it.

If emotivism is true, then of course debate can never be truly resolved! People might truly believe or act like their moral arguments are objective and logical and that debates can be resolved—but in reality, these arguments are merely feelings rather than truth claims, and debate is merely a tool for persuasion rather than a tool for reaching rational conclusions.

But a large portion of MacIntyre’s book is dedicated to disproving emotivism and explaining why and how the theory developed and became so popular in the first place.

I am only a third of the way through the book, but MacIntyre’s hypothesis already rings very true to me. However, I realize he has a difficult task ahead of him because a key component of his hypothesis is that people today, like the imaginary society he described, do not recognize their incomplete knowledge of the moral theories they discuss.

MacIntyre acknowledges the pushback he will inevitably receive: “The impulse to reject the whole suggestion out of hand will certainly be very strong. Our capacity to use moral language, to be guided by moral reasoning, to define our transactions with others in moral terms is so central to our view of ourselves that even to envisage the possibility of our radical incapacity in these respects is to ask for a shift in our view of what we are and do which is going to to be difficult to achieve.”

If this hypothesis is true, and I have long suspected it is, then it will require a complete overhaul of our approach to and understanding of morality.

realizing i don’t know anything

I am not here to prove that this is the case or explain how we should fix it—read After Virtue for that.

I do, however, want to discuss my realization that I do not understand morality as well as I thought I did—and I am interested to hear from others about similar experiences and how they navigated such a worldview-shattering realization.

Back in early 2021, I listened to Julia Galef’s interview with Michael Sandel (author of Justice: What’s The Right Thing To Do? and The Tyranny of Merit: What's Become of the Common Good?) in her podcast Rationally Speaking. In the interview, Julia questions Michael about his use of the word dignity in his moral arguments, and she claims that dignity seems to be used simply as an expression of aesthetic reactions or moral intuitions. He pushes back, and the debate gets… interesting.

Their exchange on dignity is a bit long. Still, I am going to include most of it because it is the perfect illustration of the world MacIntyre described—one in which emotivism (again, that all claims of moral truth are, in reality, merely preferences) runs wild and debates are irresolvable as a result. Pay close attention! (And consider listening to the entire episode; they go on to debate consensual cannibalism and other interesting topics, not included in the transcript below.)

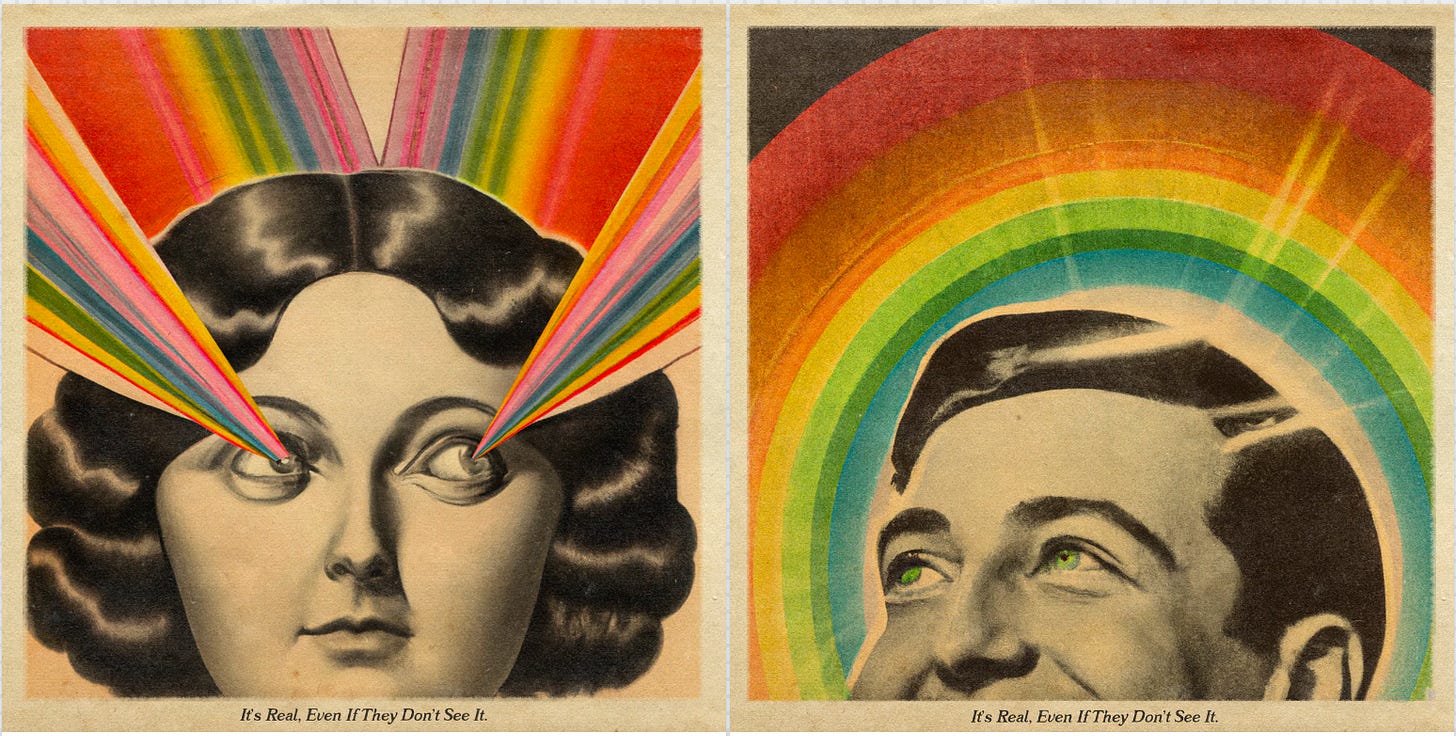

Julia Galef: One thing that made me a little hesitant in reading the book is that you'll often make statements like, "Such and such degrades a norm," or "Such and such degrades a person." An example — people selling rights to advertising on their homes or cars, or even on their person, to companies, degrades them. And it sounded, at least on my reading, that you were speaking as if this was a self-evident fact that everyone agrees on.

And in the case of people selling advertising on their bodies, I kind of share your intuition… but in general, when people say that something degrades another person, they're often speaking for that person in a way that that person themselves wouldn't agree with.

Like, people have said that it degrades someone when they strip for money. Or it degrades someone when they have sex before marriage. Or when they masturbate. And in many cases, I just feel like: “Who are you to speak for me about what degrades me?”

And so I was just wondering if you felt that your observations, or your intuitions about what is degrading — do you see those as your own personal intuitions that you understand other people might disagree with? Or do you think you're observing a thing that everyone else should also agree with?

Michael Sandel: Well, I don't think it's simply a matter of reporting one's personal intuitions. I think these judgements can be contestable, but if you believe at all that there is such a thing as human dignity, then you must also think there are certain choices or acts that are contrary to human dignity — even though we consent to them, even though we may impose them on ourselves.

Now, it can be contestable and open to argument. Take some of the examples you gave. Take the example of sex work. The debate about sex work is typically a debate about whether selling one's body for sex is or isn't a violation of human dignity. The tattoo advertising, if I sell space on my forehead to a casino, which is one of the cases that I report in the book, and install a tattoo on my head for the casino in exchange for money — some would say, and I would be inclined to agree, that that's a violation of human dignity, that use of oneself as a walking billboard for a casino. There are others who might disagree.

So there can be disagreements about what counts as a violation of human dignity, and we can reason about this. These are competing moral conceptions, competing conceptions about what it is to be a person, what respect for our own humanity consists in. And they may involve competing intuitions, but I think they are open to argument and debate. Just like debates about justice generally, or the common good are open to reason, to argument and debate.

Julia Galef: Well, at least in arguments about justice, you can appeal to thought experiments like the veil of ignorance: “What rules would you want if you didn't know your place in society ahead of time?” Or golden rule-type arguments.

But in the discussions of what counts as “degrading” or what counts as a “violation of human dignity,” I've never seen any arguments that appeal to shared principles or premises. It always seems like people are just sharing their own aesthetic reactions, or their own moral intuitions, and there's no way to appeal to principles that other people don't already share. What's your vision of how we should adjudicate these disagreements about what counts as a violation of human dignity?

Michael Sandel: Now Julia, if you don't think moral argument and moral persuasion are ever possible about anything—

Julia Galef: Oh no, I do.

Michael Sandel: Okay.

Julia Galef: I was trying to make the distinction between cases where I think it is possible, where we can agree on shared premises, and cases where it doesn't—

Michael Sandel: I don't think that distinction holds up, for the following reason.

Take a debate about human dignity that is also a debate about justice: the debate about whether torture is ever justified. Now, one of the most powerful moral arguments against the permissibility of torture is, even if it would elicit information that would serve the common good, is that it's a violation of human dignity that is categorically wrong. This would be a Kantian argument that a torture violates human dignity. So there is a conception of human dignity at stake here. And the debate is whether torture in all circumstances is categorically wrong because it violates human dignity.

So I don't think that there's a clear distinction between moral arguments about justice and moral arguments about human dignity, simply because the alleged violation of human dignity involves the way we treat ourselves rather than the way we treat others.

I don't think it makes it less susceptible of argument than debates about justice, where we do appeal to norms. We don't know whether there's a shared premise or not, until we carry on the argument, until we give it a try. This is true generally of moral argument. It's not that we say, "All right, let's first agree on first principles, and then we'll know whether or not we can persuade one another." We may not know that until the activity of persuasion and reasoning takes place.

— Rationally Speaking podcast, episode 247: The moral limits of markets / The problem with meritocracy (Michael Sandel)

I imagine that in most debates about dignity, the person disagreeing with Michael (i.e., the person in Julia’s position) would have simply argued that those examples are not violations of human dignity and given various reasons to support their claim.

But Julia did something I rarely see in debates today: before starting the debate on dignity, she took a step back to clarify his definition of the concept.

And in response to Michael’s final point: why shouldn’t we first agree on (or at least discuss!) first principles so we can understand whether or not persuasion is even a viable outcome of our debates? If we want these debates to be conclusive and have an impact, isn’t that what we have to do? Otherwise, what are we even arguing about and… why?

When I first listened to this episode, I went into a sort of personal crisis for weeks and obsessed over the concept of dignity because it was at the core of everything I believed and supported regarding policies, morality, life, and even my sense of self. I argued for policies and lifestyle choices based on dignity; when I made personal decisions, I debated how they would affect my dignity. So hearing Julia, a smart person who had dedicated a lot of thought to these ideas, admit that dignity was an alien concept to her made me question everything.

I forced many debates among my friends about the concept of dignity and, in my attempts to defend it, quickly realized that my idea of dignity was very amorphous. I was not operating based on a clear definition of dignity; in fact, it was quite arbitrary, weak, difficult (if not impossible) to prove, vague, and even self-serving. All this time, I felt as though dignity—and other concepts, I came to realize—was a self-evident truth; something everyone inherently felt and understood.

How many of our debates fail because of this? And once you realize that you do not completely understand one moral concept, your entire moral framework needs to be reassessed due to the interconnected nature of moral arguments. If your understanding of dignity evolves, how does that affect your understanding of justice? And how, in turn, does that affect your views on abortion and other issues?

For Julia, consent is really her priority for the examples listed in their exchange on dignity. As long as someone is mentally sound and fully consents to something, they should be allowed to do it. (She identifies certain exceptions.) She continues: “My reaction would be to say, let's change society so that no one is ever desperate enough to have to do something like this [tattooing a corporate logo on their forehead] if they don't want to. But my reaction would not be to say—even my intuitive reaction is not to say—that they've violated some concept of human dignity. I don't feel like I intuitively know what that means.”

This is the approach I have been most comfortable with over the past few years. I intuitively feel, and try very hard to logically argue, that certain things are right, wrong, good, or bad. But right now, until I figure out what the hell any of these complex concepts mean, I am trying to shift my focus from (a) whether we should ban or punish these things that are supposedly bad, to (b) understanding why people do those things in the first place and how we can improve conditions enough to reduce their appeal.

This mentality has helped me hone my thoughts on abortion, autonomy and the right to life (which also has implications for abortion), and other topics like free will.

I really want there to be an objective moral truth out there for us to discover. I want to believe that I live in a world in which there is a universal system of morality, that good vs. bad is clear cut or at least possible to define, and that it is possible for us to find it. I realize this is asking for a lot, and I have to accept the possibility that it just might not be true. Regardless, I still think it is very worthwhile for us to collectively try to arrive at some conclusion—but first, we need to fix this crisis of moral debate we are currently plagued with.

what now?

At this stage, my post feels incomplete to me—but I think that is simply because my understanding of this topic will always be incomplete.

Funny enough, this is in sharp contrast to how I used to feel in my teens and early 20s when I thought morality was so simple — justice for everyone! peace everywhere! — and that I knew everything. Looks like there is some truth to the idea that the older you get and the more you learn, the less you know. Or something like that. What a beautiful side effect of growth! The world and life would be too boring if we knew everything, anyway.