i am me before i am anything else

are you an automaton? if so, how would you even know it? (escaping from freedom, part II)

When it comes to the expectation of subject matter in relation to identity, I think so much of it is pervasive, in that you are expected to write a certain way based on how you look. And I think this is true of all kinds of people, from straight, white men to someone who looks like myself—there’s an expectation of what one should be concerned with. Some have a wider breadth of expectation, impossibility, than others.

I always insist on my agency as a thinker. I have the right to read what I like to read. I think that is actually more radical: to insist that because I have my own mind, I will be influenced by whom I choose, and I will write what I choose.

— Ocean Vuong, in a recent interview

identity, identity, identity

Growing up, I thought about my identity a lot. And when I say a lot, I mean a lot. But I don’t mean this in a “who am I?” sort of way. Quite the opposite: everything I liked and every belief I held was labeled and quickly appended to my identity. Perhaps naively, I never panicked about who I was; I knew very well and I screamed it to the world so everyone else would know, too. I was Muslim and an Arab American. I was a photographer. Tar Heel. Floridian. Feminist. Researcher. Liberal. You get the point!

I was never just me: Sundus.

I was always all the labels I gave myself, which meant I was also always the baggage associated with each label, regardless of its validity.

The self as a concept is complex and widely debated. But regardless of what you believe, I think we can largely agree that our sense of self is precious and needs to be safeguarded from self-sabotage or violation from others.

When you define yourself around an identity label—especially if it is intertwined with an identity-driven sociopolitical movement, which is often the case—you forfeit your ability to self-govern and to discern what you genuinely believe from what others tell you to believe. You trap yourself with a rigid and unforgiving set of instructions for things you can and cannot do and think, largely informed and enforced by others who share this identity (or are interested in controlling it). By defining your self around an identity label, you necessarily allow said label to supersede your self.

Most importantly, this identity-first approach (i.e., viewing yourself and the world through your identity labels) robs you of some of life’s most beautiful gifts: growth and change. But more on that later.

Essential skills and values come under threat as well, such as critical thought, individuality, freedom, and agency. With an identity-first approach, you do not get to choose which attributes to embody anymore; the identity group (and its sociopolitical movement) chooses for you. And in extreme circumstances—which can befall any group under the right conditions—it can even become dangerous to question or disagree with any aspect of the identity group’s ideology. This becomes especially concerning once you realize that the rules of any doctrine are notoriously fickle.

Another thought: if subscribing to an identity group makes you more likely to adopt its dominant beliefs, behaviors, culture, and traditions… are you consequently less likely to create something original that can contribute to the advancement or enrichment of humanity? (It should not be surprising that so many of those throughout history who changed the world refused to live by its rules.)

Do you become less willing to live authentically—or even to explore what authenticity is to you? Do you become more likely to turn a blind eye to prevailing (and likely dangerous) mob mentalities—or even to participate in them?

Identity labels can undoubtedly be a useful lens for understanding some experiences, but only to a certain extent. I can only begin my arguments with “As a woman…” or “As an Arab…” so many times before my claims start to contradict the experiences of other women or Arabs, which ultimately creates tension for my identity.

And then what? If I am seeing the world through an identity-first lens, what happens to the image I have constructed of myself once a core part of it is challenged? In this scenario, I am forced to either:

Subscribe to additional identity labels or come up with numerous caveats to explain why my experience contradicts that of someone else in my identity group

(This is a losing strategy because I will inevitably run into the same issue for all other identities or sub-identities)

Deny the other person of their identity because it does not align with how I define it

(And start another culture war in the process!)

Endlessly redefine my identity to accommodate contradictory experiences as I learn about them

(This is an incredibly difficult task because it requires dismantling our understanding of ourselves—over and over and over and over again. And besides, who should have the authority to define the identity in question?)

Do you see the problem here? If it seems like I am making a mountain out of a molehill, I want you to consider this next section, in which I discuss the issues I and countless others encountered with this approach, and the final section, in which I argue how identity labels can erode our freedom and lead to automaton conformity.

deprived of life’s beautiful gifts: growth and change

The first time I questioned my identity-first approach was more than seven years ago when I began to outgrow a core part of my identity: my religion. Until then, quite literally my entire life was grounded in my Muslim identity. Outgrowing my religion, in this case, meant I was also outgrowing myself. (Remember: with this identity-first approach, the label supersedes the self.) Imagine the discomfort! The “self” I thought I knew so well was suddenly challenged, leaving me lost, confused, angry, and forced to rediscover the world from a blank slate.

As my discomfort continued to intensify, I asked my boyfriend how he handles situations like this. To my complete surprise, he said he has never had to—because he does not think of himself through identity labels. I was so taken aback; I had never even considered that someone could go through life without identifying with various labels and, therefore, communities larger than oneself.

I strongly resisted his approach at first, claiming that one could not possibly feel fulfillment with such an individualistic mindset. I was sure his approach, if widely adopted, would put an end to community as we know it—and I had no interest in pursuing it.

But I eventually came around to the idea of emphasizing one’s unique self over identity labels. (To be clear, this approach is not an endorsement of individualism or rejection of collectivism. There is room for both, and I needed to find that healthy balance instead of being so far on the side of collectivism.)

After letting go of the guilt associated with “losing” core parts of myself, I quickly realized how nurturing it was to function as me first. My curiosity skyrocketed because I felt safe questioning; I became less dogmatic and even grew proud of the ability to change my mind when presented with new information; my sense of self was no longer fragile and susceptible to unsolvable challenges; I realized the importance of values and character over beliefs; my empathy and compassion grew significantly. I was finally allowed to grow without fear of being reprimanded for it.

Of course, there are tradeoffs, like potentially having to navigate the loss of community that comes with outgrowing certain ideologies or identity groups—but so far the positives have far outweighed the negatives for me. Why would I want to be part of a community that rejects me the minute I express myself in a way that challenges their established set of beliefs and practices? (Also, letting go of an identity label does not necessarily mean losing the community built around the label. There are healthy ways to redefine your relationship with your community if maintaining affiliation is important—but that is a discussion for another post.)

This brings me to my next point: one way to safely grow through life and experience the enjoyment of change is to avoid identifying around labels and instead refer to your beliefs as models.

beliefs vs. models

In one of my favorite podcast episodes, Tim Urban and Jim O’Shaughnessy talk about the benefits of viewing the world through models instead of beliefs—an idea that has stuck with me since I heard it and pretty much sealed the deal of an individual-first approach to my life.

I highly recommend listening to the entire episode, but I am going to share a transcript of the beliefs vs. models portion here:

Jim: One of the things I've found was that the smarter you are, in many cases the easier it is to deceive you, because deception starts with you deceiving yourself. And if you're really smart, guess what you're going to come up with? You're going to come up with almost a bullet proof narrative about why you're right. And then that's going to be a meme that propagates very easily through your network. And because you're smart, it's going to be very difficult to get you not to believe that.

And so when I tell that to people who are obviously intelligent, I mean, at first they look at me like, why are you insulting me? And I'm saying, I'm not insulting you. I'm saying we're human beings.

We all share a human operating system, right? The primitive [brain] as you call it is optimized to 50,000 BC, an environment that no longer exists. The higher mind built the entire world that we see around us. But what you've got to understand is that most of your beliefs are wrong.

That's the other thing that I say that now, and people lose their shit. So much so that I changed it from beliefs to models. I started in my writing no longer saying, "I believe," but rather, "I have a model that posits this."

When you make that shift internally, what happens is, you release the ego from having to cling to that belief, right? Models should prove things. And models also need to be tested, right? Because you always want to see if you're right or not.

So when you change your structure to saying, hey, I have a latticework of these mental models, and I always want to test them, it's easy for your ego to say, yeah, okay. That model’s outside of you, so I'm not worried. I'm not having my very being challenged here.

And when you do that, it's like a superpower because you no longer are wed to those beliefs, that wed to emotion and create the you that you think of as you. And when you try to go against that person, you're going to lose.

Tim: You're realizing that something very crazy is going on in my brain when I say, "I believe", and it doesn't make any sense, and it's not good for me as a thinker and it's not helping me do anything. So I'm going to shift that perception. I'm going to train my primitive mind to stop thinking that way.

When you call it a model, you're not tricking yourself, you're actually unpacking yourself. You're reframing to bring your relationship with that idea to where it should be, to where it makes sense.

It's not you've spent your whole life building up this idea and this is the thing that defines you at all. The point is, I think a really good thinker is wrong a ton of times because you're a scientist. So when you say model, immediately, I'm thinking, you're talking about a science experiment. If you're an inventor and you're working on a machine and someone says, "Hey, there's a flaw here. The screw's going to come loose." No one's going to say, how dare you. You're an idiot. That's not a good inventor. The inventor is going to say, "Thank you."

— Infinite Loops, Episode 33: Tim Urban - Exploring Ourselves

Now, when I start to develop a new belief, I approach it with caution to avoid falling for the zealousness of conversion.

At this point, it might seem as though I am trying to strip people of everything that makes them… them. How else can you understand yourself if not through labels? How will others understand you? Shouldn’t you be proud of your identity and the group built around it, whether it is your religion, nationality, gender, sexuality, philosophical belief, or even artistic style?

After realizing that so many beliefs are subject to change throughout one’s life, it became obvious to me that we should instead seek to understand and live by our core personal values. The appeal here is that these values should not come under threat or change if one of your beliefs, or models, changes.

For example, if honesty is one of my most important core personal values, it should remain constant even as I transition religious beliefs, political leanings, and even art styles. My core personal values can help guide me to the beliefs and actions that are true to myself and encourage me to slowly build an integrated, coherent worldview.

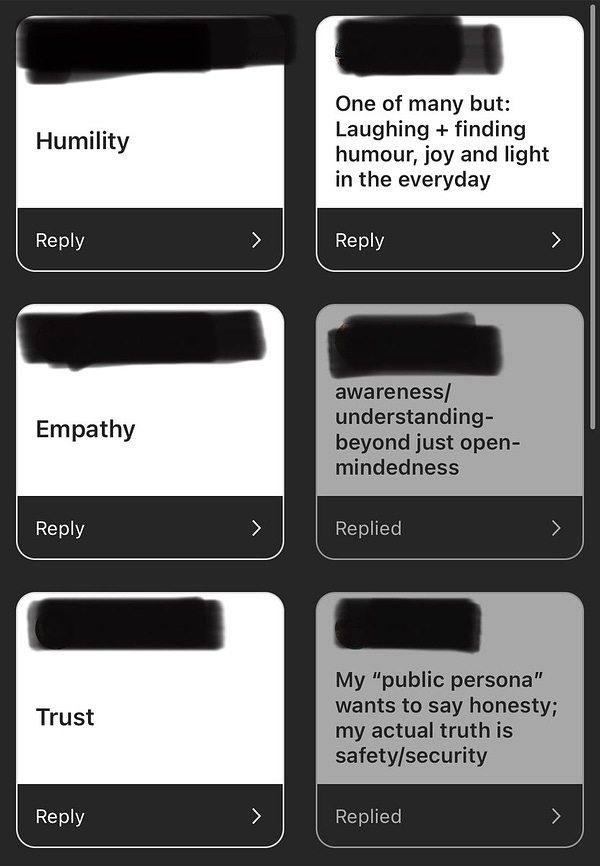

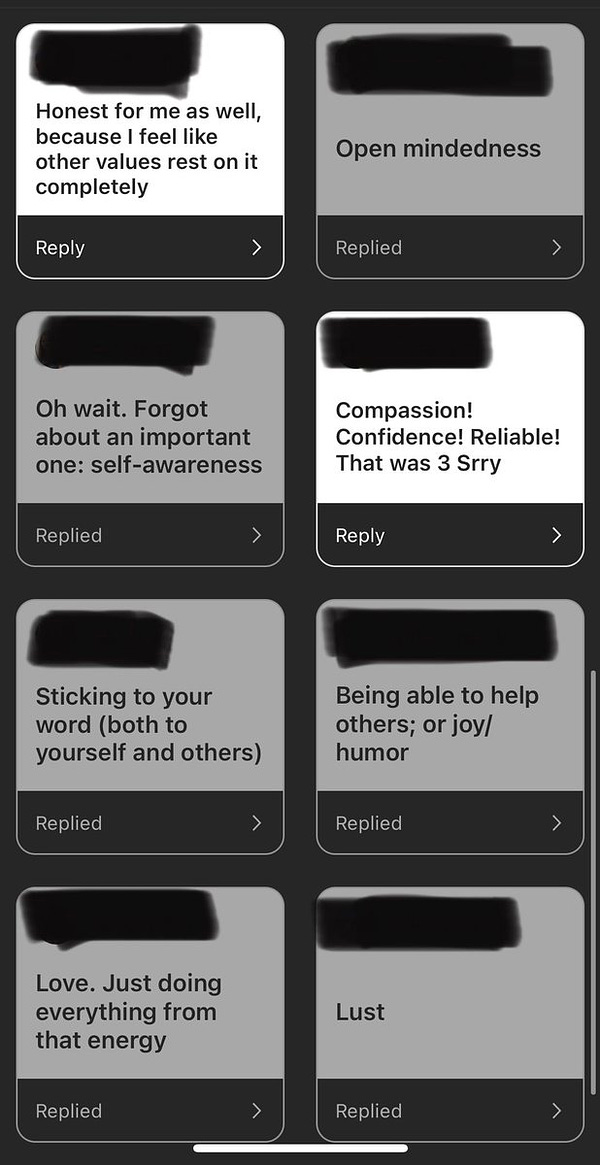

core personal values

Identity labels, which are primarily defined by the collective, are ever-changing—but you are not the agent of those changes. Understanding yourself in terms of your values and character traits is a much more practical and healthy approach. What’s the top core value that you try to practice in your day-to-day? Is it honesty? Loyalty? Taking time to think about and define the values you want to embody allows you to grow—and most importantly, outgrow—throughout life.

Of course, this doesn’t mean abandoning certain parts of your identity. Whether you like it or not, people will consciously and subconsciously label you based on looks, minimal or extensive interactions, hearsay, how you present yourself online, or the group you associate with.

When approached with caution, labels can genuinely be useful to us and others. We just have to periodically check in with ourselves to make sure we are not being controlled and consumed by our labels.

automaton conformity

Why are we so drawn to labels? In his book Escape from Freedom, philosopher and psychoanalyst Erich Fromm argues that if man experiences freedom from authoritarian rule (e.g., government, religious institution) without exercising his freedom to express his individuality while integrating himself with the world, he will feel burdened with overwhelming feelings of loneliness, alienation, and responsibility, and he will consequently try to find ways to escape his freedom.

Fromm outlines three mechanisms of escaping freedom that people commonly seek in order to overcome the feelings of anxiety and isolation that freedom from, without freedom to, produces: (1) authoritarianism via masochist or sadist tendencies, which I discuss in detail in my previous post; (2) destructiveness, which I will discuss in a future post; and/or (3) automaton conformity, the most common mechanism of escape, which I will briefly discuss here.

To put it briefly, the individual ceases to be himself; he adopts entirely the kind of personality offered to him by cultural patterns; and he therefore becomes exactly as all others are and as they expect him to be. The discrepancy between “I” and the world disappears and with it the conscious fear of aloneness and powerlessness.

The person who gives up his individual self becomes an automaton, identical with millions of other automatons around him, need not feel alone and anxious anymore. But the price he pays, however, is high; it is the loss of his self.

— Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom (pg. 184)

This is a difficult issue to overcome both individually and societally because there is a widespread belief in “free” societies that people are free to think, feel, and act as they please, and that their thoughts, feelings, and wishes are genuinely their own—but for a majority of people, who are automaton conformists, this is simply an illusion.

According to Fromm, pseudo acts, thoughts, feelings, and willingness (i.e., induced from the outside) are the rule, while genuine and indigenous ones are the exceptions.

Consider how quickly news travels today—much of which is designed to elicit moral outrage that rarely is transformed into productive action. Whether that news is truly catastrophic, merely a nuisance, or literally of no consequence, there is a pervasive idea that one must immediately adopt a strong stance on the issue, or else they will be seen as complicit in the issue, a traitor, or ignorant. This is likely a gross misunderstanding of famous quotes like: “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends” and “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor”.

In an increasingly digital age that is deteriorated by rampant mob rule and tribal thinking, the release of outrage-inducing news creates a sense of urgency to react. People’s character, status, and even reputation come under threat if they do not speak out—and, more importantly, do not speak out correctly. “Correctly” here, of course, often depends on many factors, including the group this person is affiliated with, their employer, and the goals and status they are trying to achieve.

So what happens? A news story is released, and many people will immediately respond in very predictable and scripted ways. Typically, their response is almost verbatim what their affiliated groups (e.g., religious, political) tout. If they are silent, they risk being labeled as ignorant at best or affiliates of the “opposing” group (along with a string of character attacks) at worst. This experience is especially pronounced for celebrities, influencers, and other individuals who have established an online presence in certain communities. (Seriously, why and how did we get to a point where we demand our celebrities to become moral arbiters?)

Do these people, who speak out quickly and predictably, genuinely believe what they are arguing? How much of what they say and believe is injected by their identity group? Do they feel pressure to believe and say these things, or do they subjectively feel like those beliefs are their own? Under different circumstances, would they still subscribe to those beliefs?

Are they automaton conformists?

The problem here, Fromm emphasizes, is not whether or not the beliefs are correct—the problem is whether or not the beliefs are a result of one’s own thinking. It is certainly possible that someone, through their original reasoning, can arrive at the same beliefs as the person I described above. The difference is that they came to these beliefs genuinely, whereas the aforementioned type of person came to their beliefs from outside forces—whether or not they feel or acknowledge it.

A great number of our decisions are not really our own but are suggested to us from the outside; we have succeeded in persuading ourselves that it is we who have made the decision, whereas we have actually conformed with exepctations of others, driven by the fear of isolation and by more direct threats to our life, freedom, and comfort.

In watching the phenomenon of human decisions, one is struck by the extent to which people are mistaken in taking as “their” decision what in effect is submission to convention, duty, or simple pressure. It almost seems that “original” decision is a comparatively rare phenomenon in a society which supposedly makes individual decision the cornerstone of its existence.

— Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom (pg. 197)

So, why are we so drawn to labels? When we label ourselves, we are in essence joining a community built around that label. (In the digital age, this is becoming increasingly easy to do—and increasingly lacking in meaning as well.) Ultimately, we conform to the identity group our label is affiliated with. Inevitably, affiliation with an identity group will consciously or subconsciously lead to at least some moderation of our thoughts, feelings, beliefs, and actions.

The downside, if we ever realize it, is that we lose our genuine selves; we constantly seek out approval and validation from others to feel secure in our “identity”; we become a pseudo version of ourselves; we do not know who we are anymore.

The upside? Well, the upside is so powerful that it often masks the downside, which is why so many people find themselves in a state of automaton conformity: we gain a community that (superficially) makes us feel secure; we do not feel isolated or out of place or weird; we are provided with (and rewarded for taking) shortcuts for what to believe in, what to do, and how to feel—all so we are not burdened with the important but painstaking work of determining these things for ourselves and, consequently, having to take accountability for the outcomes of our decisions; we are relieved from doubt in ourselves; we potentially gain status and the envy of others.

final thoughts

Getting rid of your labels in search of the real you might be terrifying at first, but liberation was never supposed to be easy. It’s hard work that pays off in the end.

Be kind to yourself, but at the same time skeptical and constructively critical, and you might just find the real you in there somewhere.