Something bad keeps happening to good ideas.

Good ideas are developed in specialized circles as tools that help us make sense of the world; they then slowly gain adoption among a small group of enthusiastic explorers of the idea. This is great; these groups test the idea, improve it, and discuss it in-depth — nuance and all.

Eventually, the idea enters the mainstream and is hailed as the Truth by some devout believers, or iterated nearly to death by others. This is both good and bad. Useful ideas should be widely adopted, but it seems like this is where things frequently take a turn for the worse: the idea is transformed into something utterly useless.

Has anyone else noticed this? Is there a name for this phenomenon or some research on it? I would love to hear other takes on the topic, but for now, here’s my attempt to understand what’s going on.

the four phases of idea dissemination

Over the years, I’ve noticed that many good ideas go through the following phases:

phase 1 — birth

An idea is developed by or popularized within a small circle of experts, like academics, and discussed extensively. (These ideas usually stem from the social sciences or humanities.) The idea is good and useful for better understanding some facets of life or culture.

phase 2 — exploration

Eventually, the idea is adopted by a small group of people outside this circle. It has not entered the mainstream yet but gets further developed, refined, and validated by this group of people — perhaps we can think of them as explorers or early adopters. The idea remains strong and useful.

phase 3 — deterioration

The idea finally enters the mainstream and is at the center of both online and offline discourse. Eventually, the idea starts to change: it’s no longer specific, as its original group might have intended it to be, but starts to broaden out and take on multiple meanings; the definition changes again and again and again; it’s haphazardly applied to multiple use cases; identities are formed around it. Some revere it, others fear it.

Despite (or because of?) its ubiquity, the idea ceases to be useful when it reaches this stage. It might even feel like we would be better off completely without the idea!

phase 4 — backlash

If the idea doesn’t become completely useless after it goes mainstream, at the very least it becomes annoying. Sometimes, certain groups begin to mock this idea or consider its believers cringe. They make fun of the believers by ironically using the idea. This contributes to the idea becoming useless. If the idea is useful at its core, it should be able to recover from Phases 3 and 4, though it might take a while.

These stages might apply to non-ideas as well, like social media platforms and other inventions. I will never forget how jarring it was to witness the rise and collapse of the “coolness” of Facebook for my generation after its mass adoption. (Same with Clubhouse.) I’m sure there are other examples, too, like crypto (which I believe will survive Phases 3 and 4) and AI (which currently lies somewhere at the end of Phase 2 and the beginning of Phase 3).

In fact, while I was writing this post, someone shared David Chapman’s Meaningness article, titled Geeks, MOPs, and Sociopaths in subculture evolution, about a similar phenomenon that happens to subcultures.

Chapman’s framework about subculture evolution is fascinating and illuminates the phenomenon I’ve been exploring a bit. Here’s a brief overview of his post and how it might align with my four phases:

Before there is a subculture, there is a scene. A scene is a small group of creators who invent an exciting New Thing—a musical genre, a religious sect, a film animation technique, a political theory. Riffing off each other, they produce examples and variants, and share them for mutual enjoyment, generating positive energy.

The new scene draws fanatics. Fanatics don’t create, but they contribute energy (time, money, adulation, organization, analysis) to support the creators.

Creators and fanatics are both geeks. They totally love the New Thing, they’re fascinated with all its esoteric ins and outs, and they spend all available time either doing it or talking about it.

Chapman’s creators are akin to my experts in Phase 1, while his fanatics are akin to my explorers/early adopters in Phase 2.

If the scene is unusually exciting, and the New Thing can be appreciated without having to get utterly geeky about details, it draws mops. Mops are fans, but not rabid fans like the fanatics. They show up to have a good time, and contribute as little as they reasonably can in exchange.

Geeks welcome mops, at first at least. It’s the mass of mops who turn a scene into a subculture. Creation is always at least partly an act of generosity; creators want as many people to use and enjoy their creations as possible. It’s also good for the ego; it confirms that the New Thing really is exciting, and not just a geek obsession. Further, some money can usually be extracted from mops.

However, as mop numbers grow, they become a headache. Mops also dilute the culture. The New Thing, although attractive, is more intense and weird and complicated than mops would prefer. Their favorite songs are the ones that are least the New Thing, and more like other, popular things. Some creators oblige with less radical, friendlier, simpler creations.

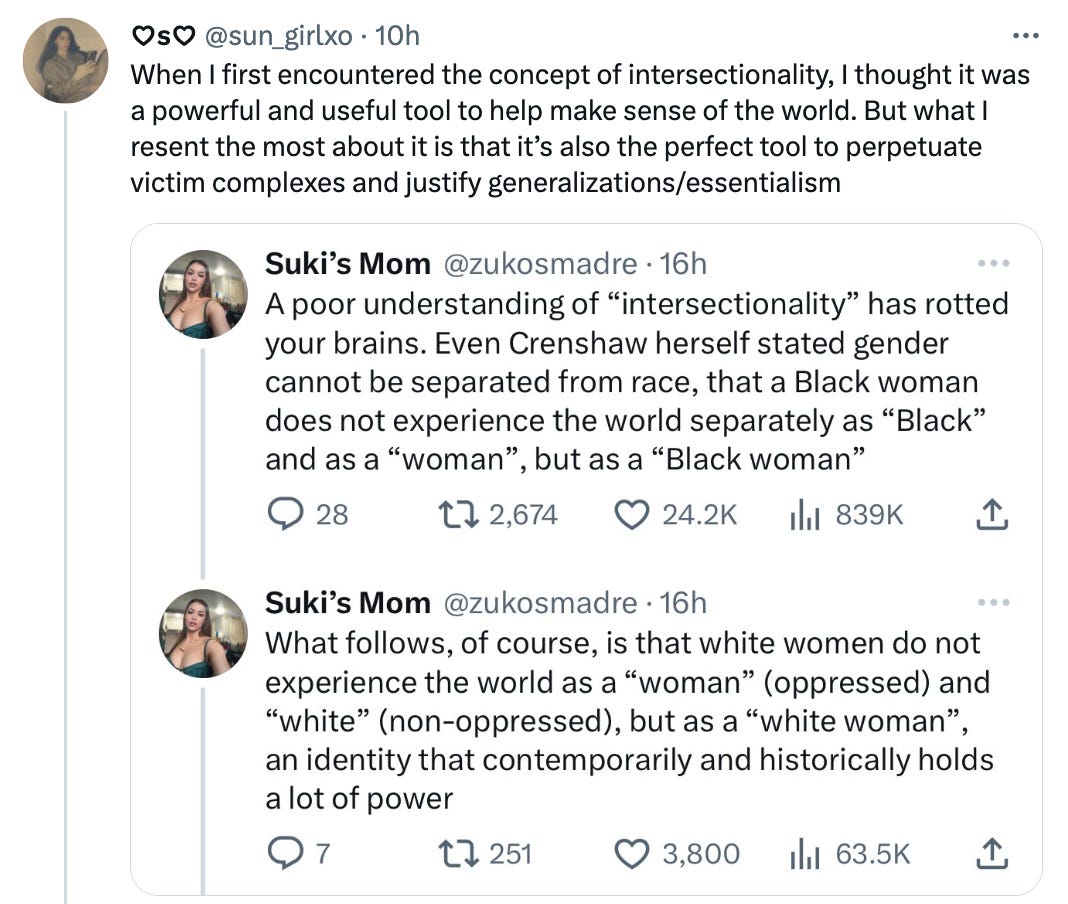

This part is closest to my Phase 3, in which an idea goes mainstream and deteriorates with popularity. Oftentimes, much like what the geeks experience, the experts and explorers/early adopters watch the evolution of their idea in horror (e.g., Kimberlé Crenshaw, the professor who coined the term intersectionality in 1989, commented on how her idea changed since it went viral: “This is what happens when an idea travels beyond the context and the content”).

I imagine that the experts and explorers/early adopters might feel some hope right as their idea enters the mainstream — but that promise quickly dies.

Fanatics may be generous, but they signed up to support geeks, not mops. At this point, they may all quit, and the subculture collapses. Unless sociopaths1 show up. A subculture at this stage is ripe for exploitation.

The sociopaths quickly become best friends with selected creators. They dress just like the creators—only better. They talk just like the creators—only smoother. They may even do some creating—competently, if not creatively. Geeks may not be completely fooled, but they also are clueless about what the sociopaths are up to. Mops are fooled. They don’t care so much about details, and the sociopaths look to them like creators, only better.

The sociopaths also work out how to monetize mops—which the fanatics were never good at. With better publicity materials, the addition of a light show, and new, more crowd-friendly product, admission fees go up tenfold, and mops are willing to pay.

This seems to be at the height of my Phase 3 — when those in the mainstream start creating businesses and identities and movements around the original idea, which contributes to the idea’s deterioration.

After a couple years, the cool is all used up: partly because the New Thing is no longer new, and partly because it was diluted into New Lite, which is inherently uncool. As the mops dwindle, the sociopaths loot whatever value is left, and move on to the next exploit. They leave behind only wreckage: devastated geeks who still have no idea what happened to their wonderful New Thing and the wonderful friendships they formed around it. (Often the geeks all end up hating each other, due first to the stress of supporting mops, and later due to sociopath divide-and-conquer manipulation tactics.)

Finally, Phase 4: chaos, resentment, fragmentation, backlash. The idea (or subculture, in Chapman’s case) is no longer useful.

from smart and new to cringe and annoying

Words like patriarchy, late-stage capitalism, colonialism, trauma-bonding, narcissism, postmodernism, neoliberalism, eugenics, critical race theory, ADHD/neurodivergent, and woke are typically at the center of such ideas. How many times have you heard one of these words thrown around with so little substance that you wondered about the validity of the idea itself?

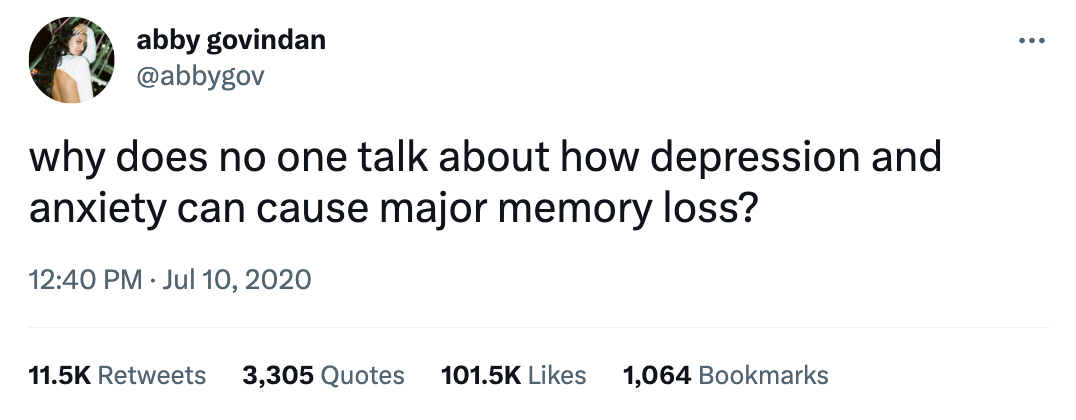

This also happens with intellectualized explanations of certain human experiences, including commonplace or universal ones. Take, for example, the following copypasta:

Of course, this touches on something real: mental illness can have serious side effects, including memory loss. But at some point, this idea entered Phase 4 and became annoying or cringe to discuss earnestly. I can imagine this idea still being discussed unironically in some circles (it might be turned into an aesthetic Awareness Raising infographic for some wanna-be mental health coach on Instagram), but it is largely categorized as a meme among younger, online generations and frequently brought up ironically for humor.

Does this mean the original idea is obsolete or invalid? Not at all. But my guess is that when it was in Phase 3, the idea was loosely applied to multiple use cases and, eventually, ceased to hold much weight. People are quick to cling to smart- and official-sounding explanations of their faults and quirks, and this is possibly what happened here.

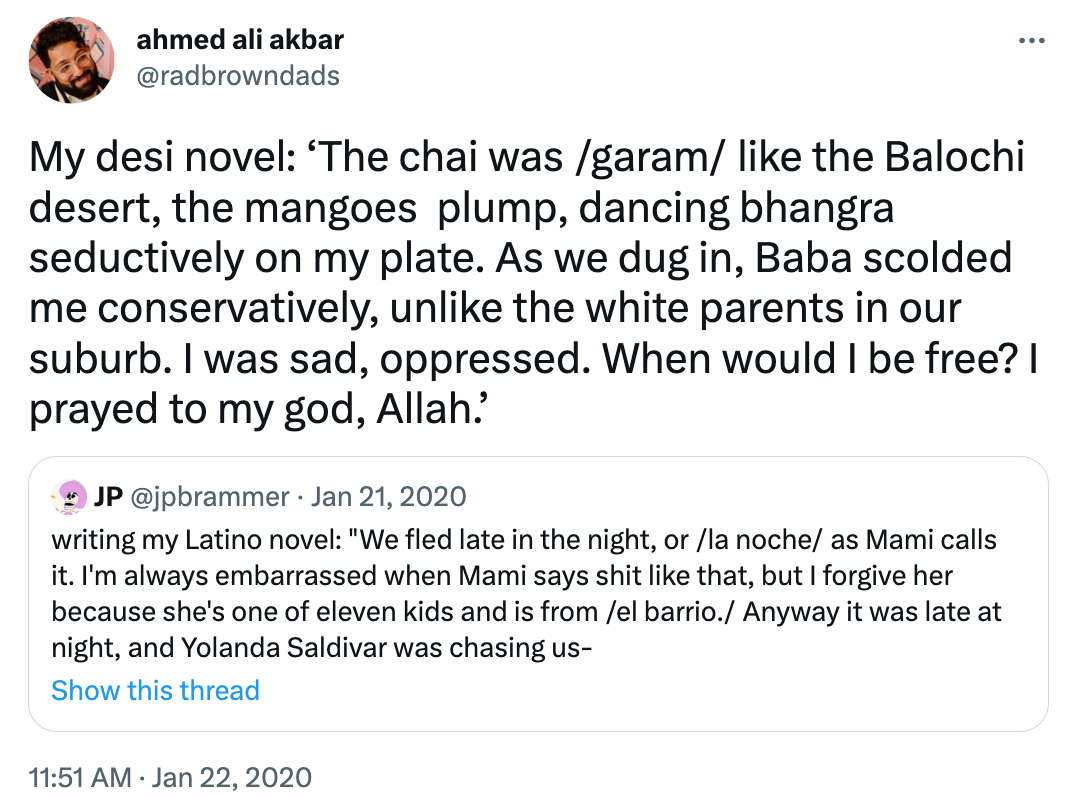

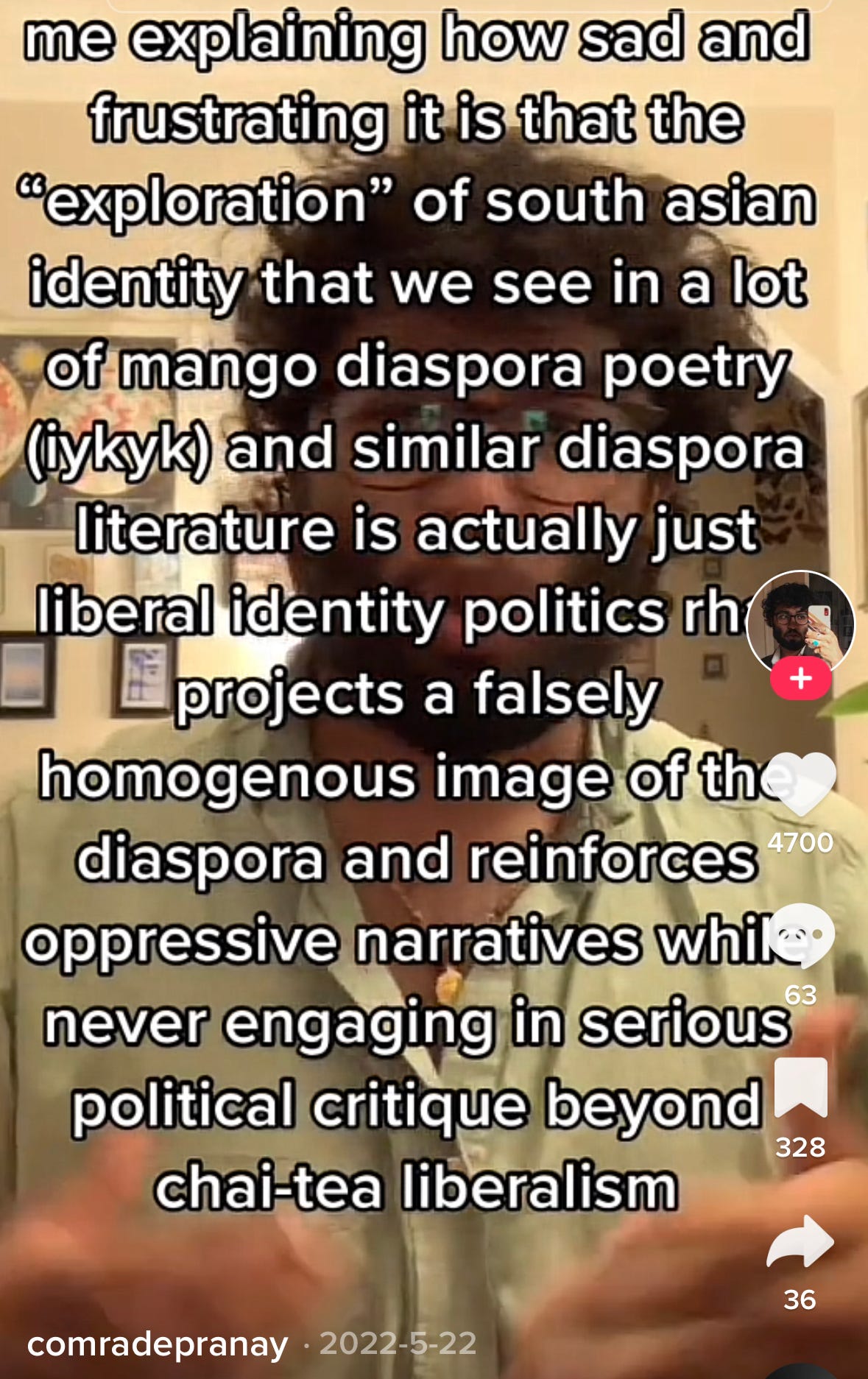

Another example is how diaspora kids describe their sense of identity as being in between their parents’ homeland and their own. What started as a useful idea was eventually ridiculed by many; the idea went through all four phases of the idea dissemination cycle.

I’m a first-generation Arab American who frequented the Middle East countless times growing up, and I empathize: growing up, I often felt like I was neither fully American nor fully Arab, but some weird in-between. I’m not alone in this, and several years ago, talking about this experience became a rite of passage for kids of the diaspora (or at least those with MENA and South Asian backgrounds).

Suddenly, blogs and podcasts and merchandise about “in-between” identities sprung up everywhere, and people ate it up. (Consider this Phase 3 of the idea dissemination lifecycle — or the proliferation of mops and sociopaths in the evolution of a subculture.)

And then, quietly, this idea (and all the art and businesses it inspired) became a target for mockery at best and heavily criticized and disdained at worst, despite the original idea being quite useful and insightful. Again, this does not mean the idea has lost all credence, despite the whims of the masses. And again, this does not mean the idea has been universally shunned; Rupi Kaur does, after all, still have a thriving fanbase. (Sorry to any Kaur fans reading my post.)

Last year, I saw the TikTok below about children of immigrants and couldn’t help but laugh because I recognized myself in it. (I also cringed hard at this realization.) I responded with my own TikTok inquiring about why good ideas often go bad.

One of my best friends messaged me and offered a very plausible explanation as to why this might happen; I think about his response to this day. To quote him:

Just saw your TikTok, you hit the nail on the head. I have a theory about why this happens, but I wonder if I’m right. It reminded me of a video ContraPoints did called “The Left.”

Basically when arcane, anti-establishment and/or marginalized concepts emerge that actually have explanatory value, like intersectionality, neoliberalism, identity politics, etc., there’s an element of these things being radical that gives a sort of intellectual superiority to people who understand them.

Because people understand them and it gives an ego boost to adopt them and talk about them as if they (among only a few people) understand them, the concepts/theories turn into an aesthetic and we ignore substance.

Then the concept is associated with the stereotype of the people adopting and talking about it vs. what it actually is, and it turns into cringe.

You can see this happening so obviously with the diaspora kid concept and “patriarchy.” Like patriarchy has been studied seriously in academia but now whenever any sort of perceived or real injustice or disparity between gender is found, (some) feminists will just say “it’s obviously because of patriarchy” but do they actually know what that means or are they trying to sound smart?

— My incredibly smart friend who perfectly explained why I felt the way I did in my TikTok

a note on bullshit

One of my favorite YouTube creators, Stephen Antonioni, uploaded a video about the fatigue that arises from fighting constant bullshit. I found that the first few minutes of his video essay highlight the repercussions of encountering so many ideas in Phases 3 and 4:

Does anyone else feel like this is all a bunch of bullshit? Does anyone else feel more stupid than they used to, despite the fact that we are swimming in a constant deluge of information every single day?

Does anyone else look at the certainty at which we speak of things today, especially online, and think for a second: wait a minute, how can we be so sure of this? How is everyone suddenly an expert on everything? How can they say, so confidently, that this one thing will make me rich? Will make me happy? Will make me confident? Will make me more beautiful? Will make me smart?

Are they speaking from life experience, or are they just regurgitating the generally accepted talking points? Are they just saying things that sound good or sound right without having done those things themselves?

When I notice that an idea is in Phase 3, I feel like I’m encountering endless bullshit and shallow regurgitations that leave me cynical and put me at risk of being amongst those in Phase 4 who mock the believers. This is not a position I would like to be in. I used to constantly find myself here, but I stopped after realizing that (a) it’s hypocritical, given that everyone contributes to Phase 3 at some point in their life, and (b) it contributes to outrage politics, which I want to see less of in the world.

memetic hygiene

My take on the idea dissemination cycle is quite cynical, so I want to discuss one more theory about idea spread. It’s not a direct comparison to the good-ideas-gone-bad phenomenon I describe in this post, but it does contextualize the idea adoption process, which might explain why things get so chaotic in Phases 3 and 4.

In my last post, “i believe, therefore it is,” I wrote about memetic hygiene and discussed Sarah Perry’s phenomenal article titled “The Limits of Epistemic Hygiene.”

In her article, Perry discusses the different types of idea contagion (or innovation diffusion) and their adoption curves:

Contagion — adoption from mere exposure; adoption occurs when people come in contact with others who have already adopted an idea or innovation; spread happens like an epidemic

Social influence — adoption of an idea already adopted by one’s in-group; adoption due to pressures to conform

Social learning — adoption occurs after one sees enough empirical evidence from early adopters to justify adoption

The adoption curve for social learning is actually two curves superimposed — and it aligns pretty well with my Phases 1 (idea creation), 2 (early adoption), and the early stages of 3 (mainstream adoption, before idea deterioration):

First, early adopters try the idea out, and adoption initially accelerates, then decelerates or even decreases as the population of early adopters is exhausted. Then, for successful innovations, a second period of super-exponential adoption follows, as the rest of the population observes the idea’s success among early adopters.

But what I found interesting is Perry’s explanation that, when adoption occurs due to social learning, people may be “learning what they can get away with — and how to get away with it.” Is this what’s happening at the height of Phase 3, when an idea is iterated endlessly and extends well beyond its original scope? The mainstream is seeing what developments they can get away with?

That might sound bad, but it doesn’t have to be. Perhaps we should celebrate the mainstream testing an idea by pushing it to its absolute limits (a practice that is integral to formal philosophical debate), because how else can we know what works and what doesn’t, what’s “true” and what’s not, and what’s possible for culture and society at large?

She uses divorce as an example of social learning, and while it doesn’t perfectly align with my four phases model, her example does provide a more nuanced picture of how and why ideas spread:

Divorce has been posited to be contagious in social networks. It is possible that many people desire to get divorced, but are hesitant to do so because they fear the social and economic consequences. If a close associate gets divorced, unhappy lovers will be able to observe an example of the consequences first-hand. If the consequences do not seem so bad, unhappily married observers may learn that they can “get away with” divorcing.

I might be able to apply her example to my framework in one of two ways:

If I split Phase 2 into two parts:

Explorers (e.g., those who are the first to get divorced in their in-group) are the first to adopt an idea or practice, and if it generates enough evidence that its adoption is a net good, then early adopters follow in their footsteps and adopt and further develop the idea or practice (e.g., others in the in-group feel confident enough to get divorced).Or, I can reframe Phase 3 to be less about the fragmentation and deterioration that occurs with mainstream adoption, and more about humanity’s natural (maybe subconscious) tendency to test ideas by pushing them to their limits and seeing if they can survive.

Maybe there is a Phase 5 that’s missing from my idea dissemination model. This might be the phase in which an idea, if it’s both strong and correct, survives all the bullshit from Phases 3 and 4 and truly contributes to our intellectual progress and development as a species. (For example, divorce, the internet, and bicycles all survived the limits they were pushed to in Phase 3 and the cultural backlash they faced in Phase 4.) Besides, I’m not sure it’s possible to achieve such progress without mainstream adoption and all the downsides that come with it.

Maybe it’s not so bad after all.

If I zoom out far enough, I can’t help but think that the four — maybe five — phases of idea dissemination are actually an incredible facet of the human project that we’re all fortunate to be part of.

Note from Chapman: I am using “sociopath” here in Rao’s informal sense, not a technical, clinical one.

You have an incredible way of breaking down and rationalizing a lot of internet culture things that are on my mind! Loved this post! I also wonder if social media has accelerated the phases of idea dissemination... ideas seem to go belly up (i.e go through the phases) faster than they did before widespread adoption of social media.

Really interesting piece. Do you think it's inevitable that ideas will go through some variation of the process? Or is it possibly for a sufficiently dedicated group of geeks / fanatics, armed with this model, to avoid the cringe and backlash phases by keeping the ideas "pure".